Tuesday, May 20, 2008

Marriage In Early African America

"Most of the selections I liked best are funny—affirmative, but not pretentious," she says. And by no means do all of the selections idealize love and marriage. In fact, many offer keen insights into how small slights and careless ways can seal a couple's fate.

Foster says the idea for this anthology came about nearly 20 years ago when she was researching for a different, more academic work on the writings of Frances E.W. Harper, with her sister, Cle, near their parents' home in Ohio.

"Cle, who is a retired deputy sheriff and has little patience with fluffy stuff, kept finding these writings [about marriage, courtship and love] in the archives and reading them and saying, 'Hey, this is interesting! You ought to make a book of it,'" Foster recalls.

"Love and Marriage in Early African America" was the result of that journey. "The stories we tell each other shape how we behave toward each other," says Foster. "These writings show that 'children of the sun' can love romantically and deeply. These writings weren't secret, but they weren't written for outsiders either. They were written for people like themselves, by themselves, so were much more candid and honest." ###

Contact: April Bogle, 404-712-8713, abogle@law.emory.edu Contact: Elaine Justice, 404-727-0643 elaine.justice@emory.edu WEB: News@Emory - University Media Relations

Monday, May 19, 2008

Maternal Respect Stronger Among African-American and Latina Girls

Julia A. Graber, Ph.D. Associate Professor Developmental Area Director & Associate Chair 502 McCarty C (352) 392-7001 (352) 392-7985 (fax) jagraber@ufl.edu Mailing Address: Department of Psychology University of Florida P.O. Box 115911 Gainesville, FL 32611-5911 | GAINESVILLE, Fla. — Young African-American and Latina girls treat their mothers with greater deference than do whites but their mothers take it harder when tempers flare, according to a new University of Florida study. “Within African-American and Latino families, children follow a cultural tradition that places a high value on respecting, obeying and learning from elders, and in our study they did indeed show more respect for parental authority,” said Julia Graber, a UF psychology professor. However, when African-American and Latina girls do act up, their mothers consider the arguments more intense than those reported by white mothers who clash with their daughters, said Graber, whose study is published in the February issue of the Journal of Family Psychology. |

For all girls, discipline was the only factor that influenced how much conflict they perceived in the relationship. The stricter and harsher mothers were, the less conflict their daughters reported, Graber said. However, as girls get older, stricter discipline may lead to greater conflict if girls try to disagree, she said.

The study differs from other research on mother-daughter conflict in that instead of looking at adolescence, it examines girls in middle to late childhood, at an average age of 8½, Graber said. The teenage years are naturally turbulent times for families, but understanding what happens immediately preceding them sets the stage for a smoother or rockier transition, she said.

Teen conflict is a risk for other behavior-related problems, Graber said. “It does seem that when there are higher levels of conflict, those daughters are more likely to have adjustment problems in terms of feeling more depression, sadness, anxiety and those problems,” she said.

The intensity of the conflicts aside, the study found that mothers’ and daughters’ reports of the frequency of conflict were similar, Graber said. The study, which Graber did with Sara Villanueva Dixon, a St. Edward’s University psychology professor, and Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, a Columbia University child development professor, involved 45 African-American, 23 Latina and 65 white girls recruited through fliers while in the third grade and their mothers. The girls and their families were from racially integrated, working and middle-class communities in a large metropolitan area.

The girls’ respect for authority was observed during a series of videotaped interactions with their mothers. Daughters were scored on their listening behaviors, which included attending to their mothers when their mothers were speaking, acknowledging their mothers’ comments and not interrupting their mothers. They also were evaluated for defiant behaviors, such as disobeying their mothers’ requests, being unwilling to cooperate with their mothers and ignoring their mothers during the interaction.

Not only do children need to be more aware of the expectations their parents have for them, but mothers may also want to reassess their feelings about particular issues, she said.

“The challenge for African-American and Latina mothers is they are in an environment where their children are potentially getting messages at school, on television and elsewhere about what normal childhood behavior is like that may conflict with their own expectations for these behaviors,” Graber said.

“In the higher conflict families where mothers and daughters are arguing much more often there seems to be less productive resolution going on and less learning of those skills,” she said. “Everybody feels mad afterwards rather than feeling the potential of moving forward.”

“This is a fascinating study that enhances our understanding of ethnic and racial differences in parent-child relationships,” said Judi Smetana, a University of Rochester psychologist. “One of its strengths is that it examines in a very careful and detailed way how different cultural values are expressed in mother-daughter interactions and how those values influence the quality of family relationships.”

Writer: Cathy Keen, ckeen@ufl.edu, 352-392-0186 Source: Julia Graber, jagraber@ufl.edu, 352-392-7001 WEB: UF College of Liberal Arts and Science

Sunday, May 18, 2008

Black Womanhood Images, Icons, and Ideologies of the African Body

Hood Explores Views of Black Womanhood Through Time and Across Continents

HANOVER, NH--This spring, the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College will open a major traveling exhibition that explores the historical roots of a charged icon in contemporary art--the black female body. Black Womanhood: Icons, Images, and Ideologies of the African Body was organized by the Hood Museum of Art and will be on view from April 1 to August 10, 2008.

The exhibition will explore the complex perpetuation of icons and stereotypes of black womanhood through the display of over one hundred sculptures, prints, postcards, photographs, paintings, textiles, and video installations by artists from Africa, Europe, America, and the Caribbean. Presented in three separate but intersecting sections, Black Womanhood reveals three different perspectives--the traditional African, Western colonial, and contemporary global--that have contributed to current ideas about black womanhood.

Juxtaposing traditional African with Western colonial-era images of African women, the second section of the exhibition reveals how the female form was used in photographic media during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to promote and disseminate racist notions about African women and black womanhood. Visitors will encounter historic photographs and postcards of the black female body created by both Western and African photographers, whose images of African and African-descended women conveyed racist messages, especially when shown out of context in the West. Ranging from ethnographic depictions of sexualized racial "types" to "Mammy" figures, from Josephine Baker in Banana Skirt to an African mother carrying a child on her back, the perpetuation of such colonial icons in the Western imagination contributed to the negative black female body images that continue to impact people today.

The third section of Black Womanhood features works by contemporary African and African-descended artists from Africa, Europe, the Caribbean, and the United States. New works by emerging South African artists Zanele Muholi, Senzeni Marasela, and Nandipha Mntambo will be exhibited for the first time in this country, as will a new sculpture created especially for this exhibition by the African American artist Joyce Scott. Also featured in the exhibition are well-established contemporary artists living in Africa and Europe such as Hassan Musa, IngridMwangiRobertHutter, Etiyé Dimma Poulsen, Sokari Douglas Camp, Emile Guebehi, Magdalene Odundo, Berni Searle, Fazal Sheikh, Angèle Essemba, Malick Sidibé, Penny Siopis, and Maud Sulter. African and African-descended artists living in the United States include Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons, Lalla Essaydi, Wangechi Mutu, Kara Walker, Alison Saar, Carla Williams, Carrie Mae Weems, and Renée Cox.

By contrasting historic representations of the African female body with contemporary representations of black womanhood, the exhibition peels back the layers of social, cultural, and political realities that have influenced the creation of stereotypes about black women. Over the last two centuries, representations of the black female body have evolved into obstinate stereotypes, leaving behind a trail of romanticized, eroticized, and sexualized icons. For example, since the end of the nineteenth century the Mangbetu woman, with her elongated forehead and halo-like coiffure, has been an icon of the seductive yet forbiddingly exotic beauty of African women. This is due both to the Western colonials who portrayed the beauty of Mangbetu women in widely disseminated photographs and postcards, and to the innovative Mangbetu artists who capitalized on this European fascination by decorating their non-figurative arts, such as musical instruments and pottery, with the sculptural form of the Mangbetu female head. Today, contemporary artists such as Magdalene Odundo and Carrie Mae Weems are recycling African and Western representations of Mangbetu women from the colonial era to comment on different aspects of black womanhood. While Kenyan-born artist Odundo creates ceramic sculptures that celebrate the enduring beauty of Mangbetu womanhood, African American artist Weems critiques the complicity of colonial-era photography in the creation of stereotypes of black womanhood in her installation From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried.

The exhibition is not an attempt to present a survey of images of the black woman throughout human history, nor is it a survey of black female artists. Rather, Black Womanhood offers a focused examination of a selection of iconic representations of the black female body that reveals how these images have affected African and African-descended artists. In this manner, the exhibition promotes and encourages a deeper understanding of the various ways in which ideas about and responses to the black female body have been shaped as much by past histories as by contemporary experiences. Curator Barbara Thompson states, "The exhibition provides the opportunity to raise awareness about the history of stereotypes of black womanhood and the continued impact they have not just on artists today but on all of us living in the global community."

The exhibition will be accompanied by a 370-page illustrated catalogue published by the Hood Museum of Art in association with the University of Washington Press in April 2008. Curator and contributing editor Barbara Thompson has compiled essays on representations of and ideologies about the black female body as presented through traditional African, colonial, and contemporary perspectives and written by artists, curators, and scholars including Ifi Amadiume, Ayo Abiétou Coly, Christraud Geary, Enid Schildkrout, Kimberly Wallace-Sanders, Carla Williams, and Deborah Willis. More than two hundred historical and contemporary images illustrate the essays that reveal the multiple levels through which social, cultural, and political ideologies have shaped iconic images of and understandings about black women as exotic Others, erotic fantasies, and super-maternal Mammies. The exhibition and its accompanying catalogue make a valuable contribution to ongoing discussions of race, gender, and sexuality, promoting a deeper understanding of past and present readings of black womanhood, both in Africa and the West.

The exhibition is generously funded by a grant from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, the William B. Jaffe and Evelyn A. Hall Fund, the Leon C. 1927, Charles L. 1955, and Andrew J. 1984 Greenbaum Fund, the Hanson Family Fund, and the William Chase Grant 1919 Memorial Fund.

About the Hood

The Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College is an accredited member of the American Association of Museums (AAM) and is cited by AAM as a national model. The Hood is located in the heart of downtown Hanover, N.H., in an award-winning building designed by Charles Moore. The museum’s outstanding and diverse collections include American portraits, paintings, watercolors, drawings, silver, and decorative arts, European Old Master prints and drawings, paintings, and sculpture, and ancient, Asian, African, Oceanic, and Native American collections from almost every period in history to the present. The Hood regularly displays its collections and organizes major traveling exhibitions while featuring major exhibitions from around the country. The museum provides a rich diversity of year-round public programs.

General Information

Admission is free of charge. Operating hours: Tuesday through Saturday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.; Wednesday, 10 a.m. to 9 p.m.; Sunday, 12 noon to 5 p.m. The Hood Museum of Art Gift Shop offers items inspired by the collections and exhibitions. The Hood is wheelchair accessible and offers assistive listening devices. For further accessibility requests, please contact the museum. For more information about the collections, exhibitions, and programs, visit www.hoodmuseum.dartmouth.edu.

Contact: Sharon Reed, Public Relations Coordinator (603) 646-2426 Sharon.reed@dartmouth.edu On the Web: Black Womanhood Images, Icons, and Ideologies of the African Body

Saturday, May 17, 2008

Racism not an issue in firing of NBA coaches

Fort said the NBA is the most integrated professional sport, so the results are not all that surprising, but they are significant.

The market for coaches in the NBA works like any other healthy labor market is ideally supposed to work—coaches must perform. By using the same scoring method researchers used, owners can calculate their current coach's value, or technical efficiency, by how many wins were produced. It appears that many owners already use the score system, since the league average score was about 13 percent higher than the average score of fired coaches, according to the paper. This is a valuable tool when setting salaries, Fort said.

Fort stresses that there are many types of racism in professional sports and the study looked at only one type over a three-year period. It does not mean that racism is absent in hiring or salary decisions in the NBA, or in the more general networking relationships among players and coaches, he said.

Fort and colleagues looked at 27 coaches of color over a three-year period. They chose the NBA because there are enough African American coaches to have a reliable research sample, Fort said. In contrast, an earlier study of hiring and firing NFL coaches found racial disparity, Fort said, but there were only five African-American coaches in the football league sample.

"As the number of coaches of color in football increases into the future, we need to see if they are still being treated in a discriminatory way," Fort said, referring to the earlier study. "This does not mean (racism in hiring coaches) is not a problem in the NFL, it means we need to look at football again."

The paper, "Race, Technical Efficiency, and Retention: The Case of NBA Coaches," appears in the recent issue of International Journal of Sport Finance. Co-authors on the paper include Young Hoon Lee, of Sogang University, Seoul, South Korea, and David Berri of California State University-Bakersfield.

Contact: Laura Bailey baileym@umich.edu 734-647-1848 University of Michigan

Friday, May 16, 2008

Kara Walker: My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor PODCAST

Over the past decade, Kara Walker has risen to international prominence for visually stunning works that challenge conventional narratives of American history and the antebellum South, and is among the most provocative and prominent American artists of her generation. With biting humor, the artist comments on race, slavery and liberation, sexual attraction and exploitation, discrimination, and modernity. The lush sensuality of her work haunts the viewer as it exposes the unofficial and subjugated histories of race and slavery in America.

The exhibition features works ranging from the artist’s signature cut black-paper silhouettes and room-size tableaux, to intimate works on paper and her acclaimed recent film animations to narrate her tales of romance, sadism, oppression, and liberation. Walker’s sophisticated command of shading and line evoke the tradition of the cartoon as a preparatory study, while her silhouettes draw from the 19th century cyclorama, large cylindrical paintings without a beginning or an end. Her stunning drawings and silhouettes reflect a profound agility and attention to detail, as she combines forms in complex counterpoints of positive and negative space. Walker’s ability to fuse her technical and formal style with a corporeal aesthetic creates characters and narrative vignettes that are beautiful and tender, yet often grotesque and repugnant as well.

Walker’s scenarios put an end to conventional readings of a cohesive national American history and expose the collective, and ongoing, psychological injury caused by the tragic legacy of slavery. Her work leads viewers through an aesthetic experience that evokes a critical understanding of the past and proposes an examination of contemporary racial and gender stereotypes. Using the genteel 18th-century art of cut-paper silhouettes, Walker’s compositions play off stereotypes and portray, often grotesquely, life on the plantation, where masters and slaves engage in a profoundly unsettling historical struggle. She has said, “The black subject in the present tense is the container for specific pathologies from the past and it is continuously growing and feeding off those maladies.”

Organized deliberately as a narrative, the exhibition articulates the parallel shifts in Kara

Walker’s visual language and subject matter: from a critical analysis of the history of

slavery as a microcosm of American history through the structure of romantic literature and Hollywood film to a revised history of Western modernity and its relationship to the notion of “Primitivism.”

About the Artist - Born in 1969 in Stockton, California, Kara Walker received her BFA from the Atlanta College of Art in 1991 and her MFA from Rhode Island School of Design in 1994. Since that time, she has created more than 30 room-size installations and hundreds of drawings and watercolors, and has been the subject of more than 40 solo exhibitions. She is the recipient of numerous grants and fellowships, including the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Achievement Award (1997) and, most recently, the Deutsche Bank Prize (2004) and the Larry Aldrich Award (2005). She was the United States representative for the 25th International São Paulo Biennial in Brazil (2002). She currently lives in New York, where she is associate professor of visual arts at Columbia University, New York.

Catalogue - To accompany the exhibition, the Walker Art Center has published a 418-page illustrated catalogue containing critical essays by scholars and cultural critics on the myriad social, racial, and gender issues present in Kara Walker’s work by exhibition curator Philippe Vergne; cultural and literary historian Sander L. Gilman; art historian and critic Thomas McEvilley; art historian Robert Storr; and poet and novelist Kevin Young. The publication features more than 150 four-color images of the artist’s work, a complete exhibition history and bibliography as well as an illustrated lexicon of the recurring themes and motifs in the artist’s most influential installations by Yasmil Raymond. Kara Walker has contributed a 36-page visual essay to the catalogue, which is distributed by D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, Inc.

Kara Walker: My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love was organized by the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. It is made possible by generous support from the Henry Luce Foundation, the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., the Lannan Foundation, the Peter Norton Family Foundation, Linda and Lawrence Perlman, and Marge and Irv Weiser.

Additional support is provided by Jean-Pierre and Rachel Lehmann.

Major support for the Hammer Museum’s presentation is provided by The Broad Art Foundation and The Joy and Jerry Monkarsh Family Foundation.

It is also made possible through the generosity of the Lannan Foundation, Susan and Larry Marx, Harvey S. Shipley Miller, George Freeman, and The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation. Public programs for the exhibition are supported by Catherine Benkaim and Barbara Timmer.

RELATED:

- The Whitney Museum of American Art: Kara Walker: - “Ms. Walker’s style is magnetic…Brilliant is the word for it, and the brilliance grows over the survey’s decade-plus span. And then there is the theme: race. It dominates everything, yet within it Ms. Walker finds a chaos of contradictory ideas and emotions.” The New York Times, review by Holland Cotter

- The Art of Kara Walker - This Web site is an educational resource developed in conjunction with the Walker Art Center exhibition Kara Walker: My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love,

- Hammer Museum: Kara Walker - Kara Walker: My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love is the first comprehensive presentation of this remarkable African American artist’s career.

- PODCAST Hammer Conversation: Kara Walker - Artist Kara Walker discusses her work in the exhibition My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love with Hammer Museum Chief Curator, Gary Garrels.

contact: sstifler@hammer.ucla.edu WEB: Hammer Museum

Thursday, May 15, 2008

African American Votes are Up for Grabs

Fredrick C. Harris's research interests include American Politics with a focus on political participation, social movements, religion and politics, political development, and African-American politics. Publications include Something Within: Religion in African-American Political Activism (Oxford University Press, 1999), which was awarded the V.O. Key Award for the Best Book on Southern Politics by the Southern Political Science Association, the Distinguished Book Award by the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion, and the Best Book Award by the National Conference of Black Political Scientists; Countervailing Forces in African-American Civic Activism, 1973-1994 with Valeria Sinclair-Chapman and Brian McKenzie (Cambridge University Press, 2006), which received the 2006 W.E.B. DuBois Book Award from the National Conference of Black Political Scientists; and Black Churches and Local Politics: Clergy Influence, Organizational Partnerships, and Civic Empowerment with R. Drew Smith (Rowman and Littlefield, 2005). Fredrick Harris | Survey Determines African American Votes are Up for Grabs; Political Scientist Also Finds Strong Support for Reforming the Nomination Process Slight majority of blacks feel they should stand together in politics, but a significant majority feel they should not always vote for a black candidate New York, January 29, 2008-An opinion survey on "Racial Attitudes and the Presidential Nomination," conducted by Fredrick Harris, Professor of Political Science at Columbia University and director of the Center on African American Politics and Society, has determined that African-American votes are up for grabs for both leading candidates of the Democratic Party and the skin color of the candidate will not automatically translate in African-American votes. One of the largest racial differences in attitudes was in response to whether the tradition of New Hampshire holding the first primary should continue. Nearly 60 percent of blacks, compared to 44 percent of whites think the tradition should be eliminated. "The study reveals the enormous value black voters place on diversity in evaluating the effectiveness of the presidential nomination process," said Fredrick Harris. "Like most voters, blacks value the process producing a candidate that can win the general election, but they place far greater emphasis on the process giving minorities a voice, and producing an ideologically and regionally diverse ticket. Clearly, black voters are both pragmatic and idealistic, balancing candidates' electability with candidates' commitment to racial, regional and ideological diversity." Electability is a value deemed as important by both blacks and whites, with blacks placing a greater emphasis on the system producing a candidate who can win the general election. About three quarters of blacks (76%) compared to 65 percent of whites think that producing a winning candidate is very important. However, the starkest difference in responses is the importance placed on giving minorities a voice in the nomination process-blacks and other minorities want their issues and interests addressed during the nomination process. |

In the survey, 61 percent of blacks identified as Democrats, only 6 percent as "Republicans" and 24 percent said they were independents.

About the Survey

The survey presents the results of a rare survey exploring racial attitudes toward the presidential nomination process. The study examines racial differences in opinions on the current system of selecting presidential nominees and gauges attitudes on whether the current process should be reformed.

The study reports findings on how feelings of group solidarity among blacks influence their candidate preferences as well as citizen's perceptions on whether the 2008 election cycle will produce a fair and accurate count of the vote. In the context of African American politics, the 2008 presidential election cycle presents black voters with a unique opportunity to play a pivotal role in determining the outcome of the Democratic presidential primary, as well as the November general election.

Contact: Tanya Domi, 212-854-5579 or td207@columbia.edu Web: Institute for Social and Economic Research and Policy

Wednesday, May 14, 2008

Thurgood Marshall wins against separate but equal with Brown v. Board of Education

When it reached the Supreme Court, the litigation known as Brown v. Board of Education included five consolidated lawsuits from four states, including South Carolina (from Clarendon County, see photos of Paxville, Clarendon County, schools) and Kansas. The Topeka, Kansas, case involved grade-schooler Linda Brown, who had been obliged to attend a black school 21 blocks from her house. There was a white school only seven blocks away.

Significantly, the trial court had denied the Kansas plaintiff (technically, the plaintiff was Linda Brown's father, the Rev. Oliver Brown) relief by finding that the segregated black and white schools there were of comparable quality. This gave Marshall the chance to urge that the Supreme Court at last rule that segregated facilities were, by definition and as a matter of law, unequal and hence unconstitutional.

On May 17, 1954, a unanimous Supreme Court vindicated Marshall's strategy. Citing the Clark paper and other studies identified by plaintiffs, the Supreme Court ruled decisively:

... in the field of public education the doctrine of "separate but equal" has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated ... are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Education attorney Deryl W. Wynn, a member of the Oxford University Roundtable on Education Policy, has said of the significance of Brown,

Here was the highest court in the land essentially saying that something was wrong with how black Americans were being treated. ... I remember my father, who was a teenager at the time, saying the decision made him feel like he was somebody. ... On a personal level, Brown's real legacy is that it serves as a constant reminder that each child, each of us, is somebody.

The Court did not specify a timeframe for ending school segregation, but the following year, in a group of cases known collectively as "Brown II," Marshall and his colleagues secured a Supreme Court ruling that desegregation proceed "with all deliberate speed."

Even then, resistance continued in parts of the South. In September 1957, when black students were forcibly turned away from Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, Marshall flew to the city and filed suit in federal court. Marshall's victory in this case set the stage for President Dwight Eisenhower's declaration of September 24: "I have today issued an Executive Order directing the use of troops under Federal authority to aid in the execution of Federal law at Little Rock, Arkansas. ... Mob rule cannot be allowed to override the decisions of our courts."

Ultimately, Marshall would obtain another Supreme Court decision, this one ordering the immediate desegregation of the Little Rock public schools.

In 1956, Marshall – using Brown as the key decision – came to the legal rescue of Martin Luther King Jr. and his followers in the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott. The boycott began on December 1, 1955, sparked by Rosa Parks' brave refusal to relinquish her seat on a segregated municipal bus to a white man. It was Marshall and the NAACP's legal team who argued for Montgomery's blacks before the courts. A November 13, 1956, Supreme Court ruling held unconstitutional the policy of relegating blacks to the back of the bus. The city of Montgomery yielded and the boycott succeeded at last.

Although many dedicated professionals worked with him, no American contributed more than Thurgood Marshall to the dismantling of legal segregation. Few could boast of a greater record of achievement, but Marshall's career of public service had only begun. He would support the cause of civil rights for all at the highest federal level, as the first African American appointed to the Supreme Court.

[Michael Jay Friedman is a staff writer with the U.S. State Department's Bureau of International Information Programs. He holds a doctorate in U.S. political and diplomatic history.]

IMAGE RIGHTS INFORMATION: No known restrictions on publication. (PUBLIC DOMAIN)

Tuesday, May 13, 2008

NASA Engineers Lorna Graves Jackson, Marceia Clark-Ingram and Tawnya Plummer Laughinghouse Honored with National Women of Color Award

HUNTSVILLE, Ala. – Lorna Graves Jackson, an engineer at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala., and a native of Everett, Mass., has received a National Women of Color Technology Award for exceptional professional and community service.

Career Communication Group's Women of Color magazine and the IBM Corporation presented Jackson with its "Technology All-Stars" award, recognizing accomplished women of color who are advanced in their careers and have demonstrated excellence as leaders at work and in their communities.

Jackson leads several employees as branch chief of the Avionics Systems Integration Branch in the Systems Engineering and Integration Division of the Space Systems Department, part of the Marshall Center's Engineering Directorate mentoring other minorities in this role. The branch includes avionics lead systems engineers that integrate various launch vehicle avionics hardware and software systems that support the Constellation Program, a NASA initiative to create a new generation of spacecraft for human spaceflight, including the Ares I and Ares V launch vehicles.

Jackson moved to Marshall's Orbital Space Plane Program Office in 2003, where she was co-lead of the Exploration System Mission Directorate Ground Infrastructure Integrated Discipline Team. She helped identify NASA facilities, facility systems and support equipment for manufacturing, testing and logistics activities to assess ground infrastructure capabilities, risk implications and development plans.

In 2005, she was named acting branch chief of the Design Integration Branch of the System Design and Analysis Division in the Spacecraft and Vehicle Systems Department. Jackson led more than 50 civil servants and contractors that supported systems engineering and integration for the Exploration Systems Mission Directorate Constellation, Shuttle External Tank and Expendable Launch Vehicle Programs. She became deputy branch chief in 2006.

Jackson was named branch chief of the Systems Management Branch of the Systems Engineering Division in the Spacecraft and Vehicle Systems Department in June 2007, where she led a team of more than 60 employees in configuration, data and risk management, and engineering planning to support complex launch vehicle systems. She began her current role as Avionics Systems Integration Branch chief in November 2007.

Jackson earned a bachelor's degree in electrical engineering from the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta in 1982. She has earned numerous honors and awards during her career, including a NASA Exceptional Achievement Medal in 2000 for technical excellence and personal dedication on the Chandra X-ray Observatory Electrical Power System development.

Jackson received the "Technology All-Stars" award in November 2007 at the 12th annual National Women of Color Science, Technology, Engineering and Math Conference in Atlanta. The conference is for minority women in information technology, computer science, information science and digital arts.

Jackson and her husband, Kurt, have two children and live in Huntsville.

Clark-Ingram is a senior material and processes engineer and advanced materials science specialist in the Laboratory Lead Engineers Office of the Materials and Processes Laboratory, part of the Marshall Center’s Engineering Directorate. She also is the primary Materials and Processes Laboratory's technical lead for interfacing with Marshall’s Propulsion Systems Engineering and Integration Office and the Shuttle Environmental Assurance initiative. This initiative supports mission execution through the life cycle of the Space Shuttle Program by identifying materials that may become obsolete as result of environment, health and safety regulations and mitigating these risks through teamwork.

Clark-Ingram began her career at NASA in 1987 when she participated in NASA's Professional Internship Program, working in the Corrosion Branch of the Materials and Processes Laboratory as a chemical engineer. From 1988 to 1992, she served as an analytical chemist in the Analytical and Physical Chemistry Branch of the lab. In 1991, she performed project management duties for the NASA Operational Environment Team as an experimental manufacturing techniques engineer in the Process Engineering Division of the Materials and Processes Laboratory.

She joined the Materials Compatibility and Environmental Engineering Branch of the Materials and Processes Laboratory in 1992 as an aerospace materials engineer, where she supported the development of a NASA-wide program plan for responding to Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Clean Air Act regulations and routinely presented NASA’s materials usage data to the EPA.

In 1995, she served as a structural materials engineer for the Materials and Processes Chemistry Group in the Materials and Processes Laboratory. She was a technical lead for the NASA, Environmental Protection Agency and Air Force Interagency Depainting Project, which tested technologies to be used as paint-stripping processes that did not adversely affect the environment.

Clark-Ingram was promoted to team lead in the chemistry group for the Materials Replacement Technology team in 2000. Her duties included technical oversight and program planning for the NASA Principal Center for the Review of Clean Air Act Regulations effort. This effort provided a proactive approach for the evaluation of potential impacts and risks to NASA’s programs due to usage restrictions of targeted materials. Additional responsibilities encompassed technical oversight for the testing operations at Marshall's Materials Combustion Research Facility and Materials Environment Test Complex.

During 2004, she was a test engineer for the Structural Strength Test Branch of the Engineering Directorate. She provided technical support for testing conducted on thermal protection systems at the Materials Environment Test Complex in support of the Space Shuttle Return to Flight effort.

Clark-Ingram earned a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering from Tuskegee University in Tuskegee, Ala., in 1985, and a master's degree in 1995 in management sciences from the Florida Institute of Technology at Redstone Arsenal’s satellite facility.

She has earned numerous honors and awards during her career, including a NASA Blue Marble Award in 2005 for excellence in environmental and energy management demonstrated in support of NASA’s mission and an exceptional service medal for outstanding technical contributions to NASA programs in 2000.

Clark-Ingram received the "Technology All-Stars" award in November 2007 at the 12th annual National Women of Color Science, Technology, Engineering and Math Conference in Atlanta. The conference is for minority women in information technology, computer science, information science and digital arts.

Clark-Ingram and her husband, Neal, have two children and live in Madison, Ala.

Laughinghouse is a materials engineer in the Nonmetals Engineering Branch and provides ceramic and ablative material expertise in support of NASA projects, such as the small solid propellant motors associated with the Shuttle Solid Rocket Booster, the Ares First and Upper Stages and the Orion Launch Abort System.

She began her career at NASA in 1990 when she participated in NASA’s Summer High School Apprenticeship Research Program. From 1991 to 1996, she served as a NASA Women in Science and Engineering scholar, which provided her a full-tuition college scholarship and summer internships at the Marshall Center.

After graduating college in 1996, Laughinghouse was a process chemist at Daubert VCI Inc. in Cullman, Ala., and in 1999, she joined Aerovox Inc. of Huntsville as a product engineer. She returned to the Marshall Center in 2004 as a materials engineer.

Laughinghouse earned a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from Spelman College and a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering from the Georgia Institute of Technology, both located in Atlanta, in 1996. In 2006, she received a master’s degree in management, with a concentration in management of technology, from the University of Alabama in Huntsville.

She has earned numerous honors and awards during her career, including selection into the 2008 NASA Foundations of Influence, Relationships, Success and Teamwork, or NASA FIRST, leadership development team. The program helps participants develop foundational leadership skills.

Laughinghouse received the Rising Star award in November 2007 at the 12th annual National Women of Color Science, Technology, Engineering and Math Conference in Atlanta. The conference supports and recognizes the accomplishments of minority women in information technology, computer science, information science and digital arts. Laughinghouse and her husband, Scott, have one daughter, and live in Huntsville.

Betty Humphery Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Ala. 256-544-0034 betty.b.humphery@nasa.gov Web: Marshall Diversity News Releases

Monday, May 12, 2008

Let Your Motto Be Resistance: African American Portraits

Much of the feedback has been surprising, Willis added. “Paul Robeson Jr. [son of the renowned entertainer and activist] told me he had never seen that image of his father.”

“I’ve been contacted by people from abroad who’ve seen the show,” she said. For example, “Polish viewers related to the civil rights images” because African-American activism affected their own pro-democracy movement.

The appeal of the portraits transcends race, culture or nationality, said Willis. “These images resonate with people everywhere,” she said.

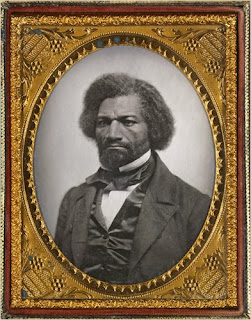

The photographs date from 1856 to 2004; the oldest is an ambrotype portrait of the 19th-century abolitionist Frederick Douglass, whose penetrating gaze attests to his forceful personality and confirms the aptness of his nickname, The Lion of Anacostia. That nickname is a reference not only to a neighborhood in Washington, but to Douglass’ stature as orator, author and champion of universal human rights.

Nearby is a photograph of Sojourner Truth, a female contemporary of Douglass who campaigned fearlessly against slavery and for women’s rights. Truth favored a plain Quaker style of dress intended to convey respectability and seriousness of purpose to a 19th-century audience that granted women far less latitude than men, said Willis.

Author, educator and activist W.E.B. Du Bois, captured in a sepia-toned image, is shown in profile, looking thoughtful and introspective. In contrast, actor/singer/activist Paul Robeson is turned directly to the viewer.

The exhibition features a mix of formal studio portraits and seemingly unposed photographs, such as a dynamic image of operatic soprano Jessye Norman singing with eyes closed and gesturing expansively with one hand. Jazz musician Louis Armstrong, flashing his trademark grin, lifts his trumpet in mid-performance, surrounded by members of his band. Dancer and choreographer Gregory Hines is a study in fluid grace as he pivots barefoot against a seamless backdrop. Pioneering figures in the civil rights movement also make their appearance, including Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks and Malcolm X.

In all of these photographs, African Americans are consciously presenting themselves as they wish to be seen, instead of accepting the identity imposed on them by the larger society, said Willis. The images created “a communal portrait of prestige and power that resisted the stereotypes of the time.”

Glamorous studio shots of film actresses Dorothy Dandridge and Lena Horne, for example, make it clear that African-American women were every bit as alluring as their white counterparts. These photographs employ “beauty as a political statement,” said Willis.

She cited a few images that are her personal favorites, including a photograph of politician Adam Clayton Powell Jr. and civil rights activist Stokely Carmichael conversing in the hallway of a congressional building. The two men are relaxed and jovial, with Powell -- a congressman -- and the much younger Carmichael personifying two generations of the civil rights struggle.

Another favorite photograph, of singer Nat “King” Cole, shows the entertainer performing at a fashionable nightclub, entirely at ease and clearly in command of the room.

Let Your Motto Be Resistance: African American Portraits opened October 19, 2007, and will be on display until March 2, 2009. More information about NMAAHC and its activities is available on the museum’s Web site. National Museum of African American History and Culture

Sunday, May 11, 2008

Gee’s Bend Quilters Create Art from Scraps of Fabric

“Whatever we had, we made the best of it,” says Creola B. Pettway in the documentary “The Quilts of Gee’s Bend.”

In 2007, Herman, who spoke at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, where 45 Gee’s Bend quilts were on exhibition, described how some quiltmakers, such as Mary Lee Bendolph, make the entire quilt at home, while others take pieced-together fabric squares to the Gee’s Bend Quilters Collective for finishing. Most now purchase their fabrics. The quiltmakers pass on their techniques and the tradition of quiltmaking to their daughters, granddaughters and other girls in the community.

“Quiltmaking is as much about the construction of community and kin networks as it is about learning to make bed coverings,” Herman told USINFO.

“So many things now are mechanized; this is handmade,” said Tosha Grantham, co-curator of the Walters exhibition. “Even if you use a machine to piece the little [fabric] squares together, a lot of people still do all the topstitching by hand.” The women come together as a community to quilt, sing and tell stories, Grantham said, “and that’s also a part of this.”

In The Quilts of Gee’s Bend, Essie Bendolph Pettway, Mary Lee’s daughter, says her brother went to college on earnings from their mother’s quilting. For Essie, quilting is a pastime. Sitting at her sewing machine, she says “I love my quilts when I make them. They be beautiful to me.”

And it is gratifying, she adds, “to think that I did some work that somebody thought was good enough to put on a wall.”

In 2003, about 50 quilters, with the assistance of Tinwood Alliance, a nonprofit foundation supporting African-American vernacular art, formed the Gee’s Bend Quilters Collective to market their quilts. Proceeds are shared by members of the collective, although some quilters also sell their work independently. Many quiltmakers have made repairs to their homes, bought appliances and donated money to their church with their earnings.

Nonetheless, Gee’s Bend (officially called Boykin, Alabama) remains economically depressed, said Herman. “They don’t just lack money, they lack the basic services.”

One reason has been its isolation. Forty-five miles from Selma, it is bounded on three sides by a bend in the Alabama River. It is an hour’s drive to Camden, the county seat and nearest place for supplies, schools and medical services. In 1962, white local authorities shut down the ferry to Camden to prevent blacks from registering to vote. Most didn’t have cars at the time. For economic reasons, the ferry service was not restored until November 2006.

Despite these circumstances, or perhaps inspired by them, Gee’s Bend quilts are “one of the most remarkable artistic practices in the United States today,” said Herman. “I’ve looked at between 800 and 900 quilts. I’ve never seen two the same.”

“What a great thing it is for [the quiltmakers] to receive this type of critical success and attention at this point in their careers,” after lacking “the material resources many Americans benefit from,” Grantham told USINFO.

“Out of necessity, the women of Gee’s Bend made these really beautiful objects that weren’t necessarily art for them, but were ways to keep warm,” said Grantham. “I think it’s a very triumphant story of perseverance and faith and creativity.”

The exhibition concluded it's run in the summer of 2007, but you may read more about the exhibition of Gee’s Bend quilts, which traveled to seven U.S. cities, on the Web sites of The Walters Art Museum and the Tinwood Alliance. The exhibition was sponsored by the Houston Museum of Fine Arts and the Tinwood Alliance. The Walters exhibition (June 15-August 26, 2007) included a gallery of 25 photos by Baltimore resident Lynda Day Clark taken in Gee’s Bend.

See U.S. Postal Service press release with photos of Gee’s Bend stamps.

(USINFO is produced by the Bureau of International Information Programs, U.S. Department of State. Web site: http://usinfo.state.gov

Saturday, May 10, 2008

NOVA documentary about Percy Julian wins AAAS Science Journalism Award

The grandson of Alabama slaves, Julian received a doctorate in chemistry in 1931 and went on to successfully synthesize an alkaloid called physostigmine, which was used to treat glaucoma -- a disease responsible at the time for 15 percent of all cases of blindness in the United States. Hired by Glidden, a manufacturer of paints and other products, he became the first black chemist to direct a chemical research laboratory. In that role he filed more than 100 patents, working with the soybean plant to develop dozens of products, from water-based paints to paper coating to protein-rich foods.

Among Julian's most significant scientific accomplishments is his work with steroids. Using stigmasterol, a plant steroid produced by soybeans, Julian was able to produce the pregnancy hormone progesterone affordably and in bulk, an achievement that helped launch the steroid industry, whose products would eventually include cortisone and the birth control pill.

By 1953, Julian had decided to leave Glidden and form Julian Laboratories, where he continued in his scientific work while establishing his lab as a haven for other black chemists, hiring more of them than any other company in America. He later sold his business for $2.3 million, becoming one of the wealthiest black entrepreneurs in the nation.

He continued to work on behalf of both science and civil rights, surviving death threats and an arsonist's attempt to burn down his house. Meanwhile, he mentored young African-American scientists and worked with the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund to bring about change in the lot of the black man in America. By 1973, he had reached a new milestone - being elected to the National Academy of Sciences - only the second African-American to become a member.

One of the challenges in developing this project was that no biography existed of Julian's life. Producer Stephen Lyons and Director Llewellyn Smith - both winners of the SJA -- were initially daunted by the fact that little written information about Julian existed, beyond a couple of articles and some scattered press clippings.

"This was hardly enough to base a two-hour program on," says Lyons. "And it meant that before we could even think about making a film, we'd have to do the kind of original research that normally goes into writing a book."

Although Julian had died in 1975, many of the people who worked with and for him were still living. So began a comprehensive effort to document the life and accomplishments of this man.

The program Web site at pbs.org/wgbh/nova/julian/ has information on Julian's scientific and career milestones as well as audio excerpts from a speech he gave in 1965, and audio interviews with people who knew him and worked with him. Visitors to the site can also follow the chemical steps involved in building a steroid and see examples of the life-saving drugs developed from ingredients in nature.

"Forgotten Genius" is one of a series of programs on the lives of scientists funded by NSF.

"'Forgotten Genius' not only gives the public a greater understanding of the scientific concepts behind Julian's significant discoveries," says NSF program director Valentine Kass. "It also tells the compelling story of a man of great intellect, personal courage and tenacity. We are proud of its contributions to the Lives in Science series." ###

Since their inception in 1945, the AAAS Science Journalism Awards have honored more than 300 individuals for their achievements. The winning journalists have helped to foster the public's understanding and appreciation of science.

Contact: Maria C. Zacharias mzachari@nsf.gov 703-292-8070 National Science Foundation

Friday, May 9, 2008

More attention should be given to African American hair care needs

Jeffrey J. Miller M.D. Associate Professor of Dermatology | Hershey, Pa. -- Hair straightening, long-term braids and frequent washing may be damaging to African American hair, and dermatologists need to be more aware and understand these differences according to a researcher at Penn State's College of Medicine. "African Americans have different hair care regimens and scalp problems compared to White-Americans," says Jeffrey J. Miller, M.D., assistant professor of medicine and a dermatologist at the Hershey Medical Center. "The purpose of this clinical research is to ultimately better serve patients. |

Miller's presentation titled, "Clinical Relevance of Hair Care in African Americans," was given today (March 12) at the American Academy of Dermatology annual meeting in San Francisco.

There is very little published or talked about concerning the differences in dermatology literature, he notes. "African Americans hair, in general, tends to be curly and dry. If curly hair is relaxed improperly, hair shaft damage can occur. The dermatologist needs to have a background in this type of hair care practice," Miller says.

Products like relaxers are fine when used correctly. Miller reports that products that relax or straighten the hair do so by opening up the cuticle of the hair, and then rearrange the bonds that go into the hair. This process can be damaging and weaken the hair shaft.

In addition to hairshaft fragility from improper relaxing, Miller also reports that another common problem is traction alopecia. "When people braid their hair too tightly, the constant tension on the hair can cause hair loss which can be permanent. Braids often need to be loosened, and hair should be rested by removing and redirecting the tension on the braids every two months," says the Penn State researcher

African Americans generally shampoo their hair less frequently than other ethnic groups, usually once or twice per week, Miller notes. If a dermatologist recommends that a patient shampoo daily, their credibility is undermined because they did not understand the needs of the patient. Because the hair is drier, shampooing more often would damage the hair, he says.

"I do know since I have been doing this research the past few years, I have a better understanding of their hair and scalp needs," says Miller.

His presentation covers hair care regimens of African Americans, treatment regimen for cosmetic alopecia or other clinical problems and a reference guide to certain hair styling terms. ###

Contact: Leilyn Perri lperri@psghs.edu 717-531-8604 Penn State

Thursday, May 8, 2008

African-American Issues in Presidential Election

Shaw is the author of "Unconventional Wisdom: Facts and Myths About American Voters," forthcoming from Oxford University Press. He worked as a strategist in the 2000 and 2004 presidential elections and serves on the national decision team for Fox News.

Learn more about the 2008 American National Election Study.

For more information, contact: Jennifer McAndrew, College of Liberal Arts, 512-232-4730; Tasha Philpot, Center for African and African American Studies, College of Liberal Arts, 512-232-3681. University of Texas at Austin

Wednesday, May 7, 2008

Dr. Charles Richard Drew, M.D., C.M., MED. D.Sc.

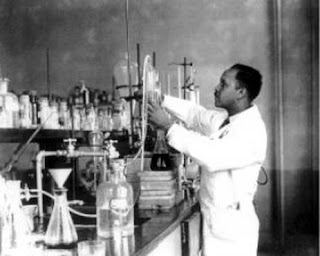

Dr. Charles Richard Drew, M.D., C.M., MED. D.Sc. - Professor Of Surgery, Howard University, Chief Surgeon, Freedmen's Hospital, Washington, D.C., 1943

ARC Identifier: 535693, Local Identifier: 208-COM-230

Creator: Office for Emergency Management. Office of War Information. Domestic Operations Branch. News Bureau. (06/13/1942 - 09/15/1945) ( Most Recent) Type of Archival Materials: Photographs and other Graphic Materials.

Level of Description: Item from Record Group 208: Records of the Office of War Information, 1926 - 1951. Location: Still Picture Records Section, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S), National Archives at College Park, 8601 Adelphi Road, College Park, MD 20740-6001 PHONE: 301-837-3530, FAX: 301-837-3621, EMAIL: stillpix@nara.gov

Production Date: 1943. Part of: Series: Artworks and Mockups for Cartoons Promoting the War Effort and Original Sketches by Charles Alston, ca. 1942 - ca. 1945. Scope & Content Note: Dr. Charles Drew - with biographical paragraphs.

Charles Richard Drew was born on June 3, 1904 in Washington D.C. to Nora and Richard Drew. Drew attended Meads Mill Elementary School,and began working as a paperboy selling copies of the Washington Times and Herald while attending school. Instead, he found work at construction sites. In 1918, he enrolled in Dunbar High School.

Dunbar was a segregated high school that had a reputation for being one of the strongest Black public schools in the country. He also was an athlete. Drew’s athleticism won him a partial scholarship to Amherst College in Massachusetts. Drew’s sister, Elsie who was ailing with tuberculosis, died of pandemic influenza in 1920. This loss is said to have influenced him to study medicine.

This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia article, Charles R. Drew SEE FULL License, Credit and Disclaimer