Martin Luther King Jr. stands with his wife, Coretta, and daughter Yolanda in 1956. (© Sandra Weiner/National Portrait Gallery) | African Americans’ Struggles, Triumphs Shown in Photo Exhibition, Museum’s inaugural exhibition shows U.S. history from unique perspective By Lauren Monsen Staff Writer

Washington -- An exhibition of 100 striking black-and-white photographs evokes the personal stories and hard-won victories of influential African Americans who helped shape the life of their nation over the past 150 years. |

Let Your Motto Be Resistance: African American Portraits -- the inaugural exhibition of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) -- traces the history of the United States from the vantage point of people who have suffered discrimination, oppression and injustice. Even now, after decades of social progress, the images from Resistance still challenge America to live up to its own highest ideals, according to Deborah Willis, curator of the exhibition.

The portraits of abolitionists, artists, writers, scientists, statesmen, entertainers and athletes illustrate the theme of “resistance” to negative stereotypes of African Americans, Willis says. “Resistance is not just physical combat, but also takes the form of visual images” that promote recognition and equality, she told America.gov.

The exhibition is housed at the National Portrait Gallery, because the NMAAHC (authorized by Congress in 2003) has not yet been built. While the new museum is awaiting its eventual site on Washington’s National Mall, its first curated show provides a glimpse of how museum officials hope to illuminate the African-American experience. |

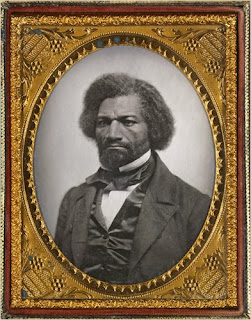

Abolitionist Frederick Douglass posed for this portrait, by an unknown photographer, in 1856. (National Portrait Gallery) |

The response to the exhibition has been “overwhelmingly positive,” said Willis. “I’ve received so many wonderful e-mail messages [from museumgoers] thanking me for introducing them to images of people they didn’t know of. Some young people said they felt there was a gap in their education.”

Much of the feedback has been surprising, Willis added. “Paul Robeson Jr. [son of the renowned entertainer and activist] told me he had never seen that image of his father.”

“I’ve been contacted by people from abroad who’ve seen the show,” she said. For example, “Polish viewers related to the civil rights images” because African-American activism affected their own pro-democracy movement.

The appeal of the portraits transcends race, culture or nationality, said Willis. “These images resonate with people everywhere,” she said.

The photographs date from 1856 to 2004; the oldest is an ambrotype portrait of the 19th-century abolitionist Frederick Douglass, whose penetrating gaze attests to his forceful personality and confirms the aptness of his nickname, The Lion of Anacostia. That nickname is a reference not only to a neighborhood in Washington, but to Douglass’ stature as orator, author and champion of universal human rights.

Nearby is a photograph of Sojourner Truth, a female contemporary of Douglass who campaigned fearlessly against slavery and for women’s rights. Truth favored a plain Quaker style of dress intended to convey respectability and seriousness of purpose to a 19th-century audience that granted women far less latitude than men, said Willis.

Author, educator and activist W.E.B. Du Bois, captured in a sepia-toned image, is shown in profile, looking thoughtful and introspective. In contrast, actor/singer/activist Paul Robeson is turned directly to the viewer.

The exhibition features a mix of formal studio portraits and seemingly unposed photographs, such as a dynamic image of operatic soprano Jessye Norman singing with eyes closed and gesturing expansively with one hand. Jazz musician Louis Armstrong, flashing his trademark grin, lifts his trumpet in mid-performance, surrounded by members of his band. Dancer and choreographer Gregory Hines is a study in fluid grace as he pivots barefoot against a seamless backdrop. Pioneering figures in the civil rights movement also make their appearance, including Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks and Malcolm X.

In all of these photographs, African Americans are consciously presenting themselves as they wish to be seen, instead of accepting the identity imposed on them by the larger society, said Willis. The images created “a communal portrait of prestige and power that resisted the stereotypes of the time.”

Glamorous studio shots of film actresses Dorothy Dandridge and Lena Horne, for example, make it clear that African-American women were every bit as alluring as their white counterparts. These photographs employ “beauty as a political statement,” said Willis.

She cited a few images that are her personal favorites, including a photograph of politician Adam Clayton Powell Jr. and civil rights activist Stokely Carmichael conversing in the hallway of a congressional building. The two men are relaxed and jovial, with Powell -- a congressman -- and the much younger Carmichael personifying two generations of the civil rights struggle.

Another favorite photograph, of singer Nat “King” Cole, shows the entertainer performing at a fashionable nightclub, entirely at ease and clearly in command of the room.

Let Your Motto Be Resistance: African American Portraits opened October 19, 2007, and will be on display until March 2, 2009. More information about NMAAHC and its activities is available on the museum’s Web site.

National Museum of African American History and Culture

No comments:

Post a Comment