Study highlights:

* An international medical group recommends African-Americans be treated for blood pressure at lower threshold levels than the general population.

* The International Society of Hypertension in Blacks’ consensus statement also suggests doctors should move from single drug therapy to combinations of up to four drugs to keep blood pressure comfortably below target levels more quickly.

DALLAS, Oct. 4, 2010 – According to a consensus statement by the International Society on Hypertension in Blacks (ISHIB), high blood pressure in African-Americans is such a serious health problem that treatment should start sooner and be more aggressive. The ISHIB statement is published in Hypertension: Journal of the American Heart Association.

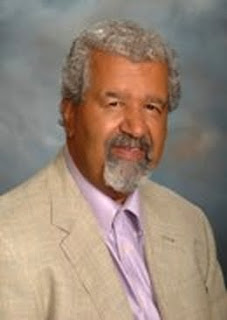

John M. Flack, M.D., M.P.H. Chair of Internal Medicine 2E University Health Center Phone: 313-745-8244 Fax: 313-993-0645 jflack@med.wayne.edu | Complications related to high blood pressure such as stroke, heart failure and kidney damage occur much more frequently in African-Americans compared with whites. “Evidence from several recently completed studies converged to convince our committee that we were waiting a little bit too long to start treating hypertension in African-Americans,” said John M. Flack, M.D., M.P.H., lead author and chairman of the Department of Internal Medicine at Wayne State University in Detroit. The update to the ISHIB’s 2003 consensus statement makes two major recommendations: First, the thresholds at which African-American patients begin treatment should be lowered. |

“We believe that these recommendations will lead to better blood pressure control, and a better outlook for African-Americans with high blood pressure,” Flack said.

Blood pressure is reported as two numbers, measured in millimeters of mercury (mm Hg). The top number represents the pressure in the arteries when the heart beats and the lower number reflects the pressure when the heart relaxes between beats.

Blood pressure below 120/80 is considered normal for healthy U.S. adults. However, the ISHIB proposes that doctors recommend lifestyle changes to lower blood pressure in otherwise healthy African-Americans with blood pressure at or above 115/75. Those changes include reduced dietary sodium (salt) and increased potassium from eating more fruits and vegetables, as well as losing weight if necessary, getting regular aerobic exercise and drinking in moderation, Flack said.

“Epidemiological data shows that 115/75 is the critical blood pressure number for adults, and every time that figure goes up by 20/10 the risk of cardiovascular disease essentially doubles. We think it makes perfect sense to start lifestyle changes at that lower threshold,” he said. “The natural history of blood pressure is that it continues to go up as a person ages. In fact, from the age of 50 and onward, Americans have a 90 percent chance of developing hypertension.”

Doctors currently begin drug therapy to reduce blood pressure in patients without a history of cardiovascular disease, diabetes or high blood pressure-related organ-damage when blood pressure is at or above 140/90. This is referred to as primary prevention. The ISHIB recommends tightening the primary prevention threshold to 135/85 for African-Americans.

In addition, the ISHIB recommends starting treatment earlier for African-Americans who have cardiovascular disease, diabetes, kidney disease or damage to target organs (the heart, brain, kidneys). This treatment, known as secondary prevention, should start when blood pressure is at or above 130/80, according to the ISHIB statement.

The ISHIB also recommends that doctors move swiftly from single-drug therapy to multi-drug therapy if one agent doesn’t lower the pressure.

“The majority of patients of any race, and certainly African-Americans, are going to need more than one drug to be consistently controlled below their goal,” Flack said. “The debate in the medical community over which single drug is best overwhelms the most pressing question: Which drugs work best together?”

Based on a review of recently completed studies, the ISHIB document provides doctors with step-by-step guidance on the best second, third and fourth drugs to add based on individual patient characteristics. The ISHIB statement provides charts with alternate multi-drug combinations so physicians have several options for keeping patients’ blood pressure under targets, Flack said.

Flack stressed that the ISHIB tried whenever possible to suggest cheaper generic drugs to keep cost from becoming a treatment barrier.

“These guidelines raise the question for addressing issues surrounding treatment strategies and goals for African-Americans with hypertension,” said Sidney C. Smith Jr., M.D., an American Heart Association spokesman and professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine in Chapel Hill, N.C. “Studies continue to accumulate that address ethnic, age and gender differences, as well as optimal therapies.”

A major comprehensive statement regarding hypertension is expected to be published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) by late 2011, Smith said.

The American Heart Association participates as a member organization in the NIH Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC) guidelines.

Co-authors of the ISHIB statement are: Domenic A. Sica, M.D.; George Bakris, M.D.; Angela L. Brown, M.D.; Keith C. Ferdinand, M.D.; Richard H. Grimm, Jr., M.D., Ph.D.; W. Dallas Hall, M.D.; Wendell E. Jones, M.D.; David S. Kountz, M.D.; Janice P. Lea, M.D.; Samar Nasser, P.A.-C., M.P.H.; Shawna D. Nesbitt, M.D.; Elijah Saunders, M.D.; Margaret Scisney-Matlock, R.N., Ph.D. and Kenneth A. Jamerson, M.D. Individual author disclosures are on the manuscript. ###

Statements and conclusions of study authors published in American Heart Association scientific journals are solely those of the study authors and do not necessarily reflect the association’s policy or position. The association makes no representation or guarantee as to their accuracy or reliability. The association receives funding primarily from individuals; foundations and corporations (including pharmaceutical, device manufacturers and other companies) also make donations and fund specific association programs and events. The association has strict policies to prevent these relationships from influencing the science content. Revenues from pharmaceutical and device corporations are available at www.americanheart.org/corporatefunding.