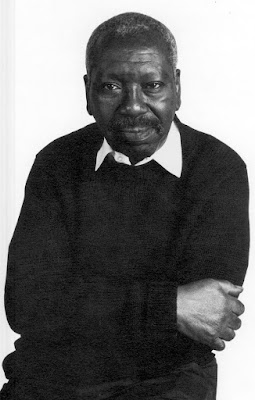

David Barton Smith, PhD. Research Professor, Center for Health Equality Department of Health Management and Policy. Phone: 215.762.7448. Email: dbs33@drexel.edu Professor Smith received his Ph.D. in Health Services Research from The University of Michigan. He was awarded a 1995 Robert Wood Johnson Health Policy Research Investigator Award for research on the history and legacy of the racial segregation of health care and continues to do research, write and give lectures on this topic at medical and law schools across the country. He is the author or co-author of five books on the organization of health services, the most recent being, Health Care Divided: Race and Healing a Nation (The University of Michigan Press 1999), and Reinventing Care: Assisted Living in New York City (Vanderbilt University Press 2003). The latter book propelled legislative reform in the regulation of assisted living in New York State. He is also author of Long Term Care in Transition: the Regulation of Nursing Homes (Health Administration Press 1981) that helped initiate quality of care reforms in that decade. | Poorer Quality of Care In Nursing Homes Linked To Racial Segregation; Nursing Homes in Milwaukee, St. Louis, and Cleveland Have Greatest Disparities. In metropolitan areas across the United States, blacks are more likely than whites to live in poor quality nursing homes, according to a study of Health Affairs. The problem is most acute in the Midwest. After ranking metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) based on disparities between blacks and whites in access to quality nursing homes, researchers found that 10 of the 20 nursing homes with the greatest disparities in quality of care were located in Wisconsin, Indiana, Ohio, and Michigan. The metropolitan area with the greatest disparity in care is Milwaukee, where blacks are more than twice as likely as whites to live in a nursing home with significant inspection deficiencies, substantial staffing shortages, and financial problems. The study showed that inequalities in care are closely correlated to racial segregation. Researchers found that nursing homes in the Cleveland metropolitan area were the most segregated, followed closely by Gary, Ind., Milwaukee, Detroit, Indianapolis, Chicago, St. Louis, Harrisburg, Pa., Toledo, Ohio, and Cincinnati (A complete list of the 147 MSA rankings is available in a separate document). At the same time, researchers found that nursing homes in the South were least likely to have unequal racial distribution of residents relative to residential racial composition. And only four Southern urban centers – Houston, West Palm Beach, Fla., Richmond, Va. and Winston-Salem, N.C. – landed in the top 20 metropolitan areas with the highest level of racial disparities in nursing home quality. The study, supported by the Commonwealth Fund, is the first to document this relationship between racial segregation and quality disparities in U.S. nursing homes. |

In their analysis, researchers looked at racial segregation in 147 MSAs, with 7,196 nursing homes, caring for more than 800,000 residents. Researchers used the Dissimilarity Index, the most common measure of residential segregation. The index indicates the combined percentage of residents of both races who would have to be relocated for there to be an equal proportion of blacks and whites in the nursing home.

The researchers found that:

* Blacks were nearly three times as likely as whites to be located in a nursing home housing predominantly Medicaid residents.

* Blacks were nearly twice as likely as whites to be located in a nursing home that was subsequently terminated from Medicare and Medicaid participation because of poor quality.

* Blacks were 1.41 times as likely as whites to be in a nursing home that had been cited with a deficiency causing actual harm or immediate jeopardy to residents.

* Blacks were 1.12 times as likely as whites to reside in a nursing home that was greatly understaffed.

"This study shows us that racial segregation has a significant impact on the quality of care received by nursing home residents," said Smith, a professor at Temple University and lead author of the study. "While it is important to eliminate disparities in care within nursing homes to achieve full equity, our research indicates that it is far more important to eliminate persistent patterns of segregation and the differences in the quality of care between nursing homes that tend to serve blacks as opposed to whites."

According to the research, blacks make up about 15 percent of all U.S. nursing home residents. Yet around 60 percent of black residents were concentrated in less than 10 percent of those homes. The 10 percent of U.S. nursing homes in which blacks reside tend to be in the bottom quartile with respect to quality, the study showed.

"Blacks and whites aren't getting different care in the same nursing homes. They're getting different care because they live in different nursing homes," said Mor, chairman of the Department of Community Health at Brown University and lead investigator on the study. "In the same urban areas, blacks are more likely to be concentrated in substandard nursing homes—homes with smaller budgets, smaller staffs and poorer regulatory performance."

"People being admitted to nursing homes understandably want to stay close to family members but exercising that choice should not put them in greater jeopardy of receiving poor quality care. The degree of the disparity in quality revealed by this study is unacceptable," said Commonwealth Fund Assistant Vice President for Quality of Care for Frail Elders, Mary Jane Koren, M.D. "If we are to ensure access to high quality health care for all we must address the stark differences in care provided by facilities that serve a predominantly minority population."

The study authors offered recommendations for policy changes that could improve the quality of care in nursing homes and potentially eliminate the disparities highlighted by the study. Their recommendations include:

* improvements to payment structures for nursing homes with a high proportion of Medicaid residents;

* closing the gap between the amount paid to nursing homes by Medicaid and private payers;

* broader regional planning in response to concerns about racial disparities; and

* ongoing monitoring of admissions practices to ensure that they meet Civil Rights Act requirements.

The Commonwealth Fund is an independent foundation working toward health policy reform and a high performance health system.

Brown University is an internationally known Ivy League institution with a distinctive undergraduate academic curriculum, outstanding faculty, state-of-the-art research facilities, and a tradition of innovative and rigorous multidisciplinary study. For more information, visit www.brown.edu

Health Affairs, published by Project HOPE, is the leading journal of health policy. The peer-reviewed journal appears bimonthly in print with additional online-only papers published weekly as Health Affairs Web Exclusives at www.healthaffairs.org. Copies of the September/ October 2007 issue will be provided free to interested members of the press. Journalists may also access content on the Health Affairs Web site after the embargo lifts by using the press username 'media' and the password 'november'. Address inquiries to Christopher Fleming at Health Affairs, 301-347-3944, or via e-mail, cfleming@projecthope.org

Temple University's Fox School of Business is the largest, most comprehensive business school in the greater Philadelphia region and among the largest in the world, with more than 6,000 students, 150 full-time faculty members and 51,000 alumni. For more information, visit www.fox.temple.edu

Commonwealth Contact(s): Mary Mahon Public Information Officer TEL 212-606-3853, cell phone 917-225-2314, mm@cmwf.org Bethanne Fox (301) 576-6359