Thursday, April 24, 2008

Many African-Americans have a gene that prolongs life after heart failure

"By mimicking the effect of beta blockers, the genetic variant makes it appear as if beta blockers aren't effective in these patients," he explains. "But although beta blockers have no additional benefit in heart failure patients with the variant, they are equally effective in Caucasian and African-American patients without the variant."

Co-author Stephen B. Liggett, M.D., professor of medicine and physiology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and director of its cardiopulmonary genomics program says the discovery adds to the accumulating evidence that genetic differences contribute to the way people respond to medications and should encourage the use of genetic testing in clinical trials to identify people who can benefit from therapy tailored to their genetic makeup.

About 5 million people in the United States have heart failure, and it results in about 300,000 deaths each year. Beta blockers slow heart rate and lower blood pressure to decrease the heart's workload and prevent lethal cardiac arrhythmias.

While Caucasians with heart failure participating in clinical studies of beta blockers have shown clear benefit from the drugs, the evidence for benefit in African-Americans has been ambiguous. The current study, reported online April 20, 2008, in Nature Medicine, identified one particular race-specific gene variant that seems to account mechanistically and biologically for these indeterminate results.

The gene codes for an enzyme called GRK5, which depresses the response to adrenaline and similar hormonal substances that increase how hard the heart works. Adrenaline is a hormone released from the adrenal glands that prompts the "fight-or-flight" response — it increases cardiac output to give a sudden burst of energy.

In heart failure, decreased blood flow from the struggling heart ramps up the body's secretion of adrenaline to compensate for a lower blood flow. Overproduction of the hormone makes the weakened heart pump harder, but eventually worsens heart failure.

Beta blockers alleviate this problem by blocking adrenaline at its receptor in the heart and blood vessels. GRK enzymes mimic this effect by serving as "speed governors" that work like the governor in an engine to prevent adrenaline from over-revving the heart, says Dorn.

The researchers — including three equally contributing co-authors: Liggett, Sharon Cresci, M.D., assistant professor of medicine in the Cardiovascular Division at Washington University and a cardiologist at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, and Reagan J. Kelly, Ph.D., at the University of Michigan — found that 41 percent of African-Americans have a variant GRK5 gene that more effectively suppresses the action of adrenaline than the more common version of the gene. People with the variant gene could be said to have a natural beta blocker, Dorn says. The variant is extremely rare in Caucasians, accounting for its predominant effects in African-Americans.

The researchers showed that African-American heart failure patients with this genetic variant have about the same survival rate even if they don't take beta blockers as Caucasian and African-American heart failure patients who do take beta blockers.

"That doesn't mean African-Americans with heart failure need to be tested for the genetic variant to decide whether to take beta blockers," Dorn says. "Under the supervision of a cardiologist, beta blockers have very low risk but huge benefits, and I am comfortable prescribing them to any heart failure patients who do not have a specific contraindication to the drug."

"This is a step toward individualized therapy," Cresci says. "Medical research is working to identify many genetic variants that someday can ensure that patients receive the medications that are most appropriate for them. Right now, we know one variant that influences beta blocker efficacy, and we are continuing our research into this and other relevant genetic variants."

The human heart has two forms of GRK: GRK2 and GRK5. The researchers meticulously searched the DNA sequence of these genes in 96 people of European-American, African-American or Chinese descent to look for differences. They found most people, no matter their race, had exactly the same DNA sequence in GRK2 or GRK5. But there was one common variation in the DNA sequence, a variation called GRK5-Leu41, the variant that more than 40 percent of African-Americans have.

To determine the effect of the GRK5-Leu41 variant, the team studied the course of progression of heart failure in 375 African-American patients. They looked for survival time or time to heart transplant, comparing people with the variant to those without. Some of these patients were taking beta blockers and some were not.

In patients who did not take beta blockers, the researchers found that those with the variant lived almost twice as long as those with the more common version of the GRK5 gene. Beta blockers prolonged life to the same degree as the protective GRK5 variant, but did not further increase the already improved survival of those with the variant.

"These results offer an explanation for the confusion that has occurred in this area since clinical trials of beta blockers began," Dorn says. "Our study demonstrates a mechanism that should lay to rest the question about whether beta blockers are effective in African-Americans — they absolutely are in those who don't have this genetic variant."

Other institutions collaborating in the study are the University of Cincinnati, Thomas Jefferson University and the University of Missouri, Kansas City.

Liggett SB, Cresci S, Kelly RJ, Syed FM, Matkovich SJ, Hahn HS, Diwan A, Martini JS, Sparks L, Parekh RR Spertus JA, Koch WJ, Kardia SLR, Dorn II GW. A GRK5 polymorphism that inhibits beta-adrenergic receptor signaling is protective in heart failure. Nature Medicine April 20, 2008 (advance online publishing).

Funding from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute supported this research.

Washington University School of Medicine's 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked third in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.

Media Assistance: Gwen Ericson Assistant Director of Research Communications ericsong@wustl.edu (314) 286-0141 WEB: Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis

Wednesday, April 23, 2008

Increasing robotics education and research for African-American students. VIDEO

Rplay is a project to create an online video game with which users can remotely control robotic dogs to play soccer. The purpose of the project is to gather learning data for the dogs, so they can eventually be taught to play the game on their own.

At Brown, the program is spearheaded by Chad Jenkins, assistant professor of computer science. “The aim is to develop and strengthen pathways from HBCUs to major research universities for minority students who want to pursue graduate degrees in computer science,” Jenkins said. “Robots are a great way to inspire students because they are interactive and fun but also pose intellectually deep challenges.”

During the summers of 2008 and 2009, Jenkins will bring an undergraduate HBCU student to campus for a research internship. Students will develop software applications that will allow robots to more effectively interact with humans, a major research focus in Jenkins’ laboratory. African-Americans now account for just 4.8 percent of almost 2 million U.S. computer and information scientists, a job category that the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects will be among the fastest growing occupations over the next decade.

“To advance computing technology and robotics, we need as many great minds in the field as possible,” Jenkins said, “so it is critical to draw in dedicated and interested students, whether they choose to work in academia or the commercial sector.”

HBCUs participating in ARTSI are Spelman College, Hampton University, Morgan State University, Florida A&M University, Norfolk State University, Winston-Salem State University, University of Arkansas-Pine Bluff and the University of the District of Columbia.

They are joined by research universities including Brown, Carnegie Mellon, University of Pittsburgh, Georgia Institute of Technology, Duke University, University of Alabama and University of Washington that will provide research internships, mentoring opportunities and lesson plans and materials. Corporate partners include Seagate Technology, Microsoft, Apple, iRobot and Juxtopia.

Activities will include:

- academic-year student research activities at HBCUs;

- summer internships for HBCU students in research university labs;

- an annual student research conference and workshop;

- local outreach at middle and high schools serving minority populations in each HBCU's community;

- national outreach through an ARTSI web portal, currently under development.;

- “viral marketing” through student-produced robotics videos on YouTube that showcase the achievements of ARTSI-affiliated students and faculty.

Contact: Wendy Lawton Wendy_Lawton@brown.edu 401-863-1862 Brown University

Tuesday, April 22, 2008

LSU spotlights strong African American marriages VIDEO

Study fills gap in positive research on African American families

BATON ROUGE – Loren Marks, assistant professor of human ecology at LSU, along with several colleagues, published one of the only studies hallmarking positive, long-lasting African-American marriages. The study, “Together, We Are Strong: A Qualitative Study of Happy, Enduring African American Marriages,” will be published in “Family Relations” in April.

“This all started about five years ago, when two of my students came up to me after class to ask me a question I couldn’t answer,” said Marks. “They asked me why there wasn’t any research done on strong, marriage-based black families like the ones they came from.”

According to the study, scholars tend to view African American families through what is known as a “deficit perspective,” a manner that emphasizes problems and negatives. “We felt it was time that someone stepped up and researched the many solid, long-lasting African American marriages that are out there,” said Marks.

This qualitative study, which relies on in-depth interviews rather than numerical data, was based on discussions with 30 African American married couples identified across the country. Four key themes rose out of the interviews:

1. Challenges to African American Marriages

Approximately one-half of African Americans – and 24 out of the 30 interviewed couples – live in inner-city neighborhoods typified by poverty, deficient schools, unemployment, street violence and high levels of stress. It is difficult to get married and stay married in such an environment.

2. Overcoming External Challenges to Marriage

Due to their stability, these marriages serve as a primary source of support for those around them. “Knocks of need,” or calls for financial, emotional and social support, come to these couples in a seemingly disproportionate amount. The couples’ household incomes weren’t high by national standards but they typically had more liquid assets than their neighbors – at least until they shared.

3. Resolving Intramarital Conflict

Like all relationships across racial and economic boundaries, each couple reported arguments, disagreements and generally being “different” from one another, but they found ways to work through their conflicts.

4. Unity and the Importance of Being Equally “Yoked”

90 percent of the couples interviewed were actively religious in the same church. Only three of the couples did not regularly attend church, instead choosing to spend Sundays home together. However, the single common factor found was that every couple was in agreement about their religious views, whatever they might be. The couples referred to this as being “equally yoked.”

“The goal of the study was to tell the stories of real people, facing real challenges and struggles, but who pull together in their marriages and continue to make it through,” said Marks. “We want young people, black and white, to see that strong, happy marriages do exist but that they don’t look like the movies. These marriages involve work, sacrifice, patience, unselfishness and commitment. It is tough, but it is possible.” ###

Contact: Loren Marks lorenm@lsu.edu 225-578-2405 Louisiana State University

Contact Ashley Berthelot LSU Media Relations 225-578-3870 aberth4@lsu.edu

Monday, April 21, 2008

Trust between doctors and patients is culprit in efforts to cross racial divide in medical research

Study shows lingering doubts and fears hamper research participation by African Americans

More than three decades after the shutdown of the notorious Tuskegee study, a team of Johns Hopkins physicians has found that Tuskegee’s legacy of blacks’ mistrust of physicians and deep-seated fear of harm from medical research persists and is largely to blame for keeping much-needed African Americans from taking part in clinical trials.

In a report to be published in the journal Medicine online Jan. 14, experts in the design and conduct of medical research found that black men and women were only 60 percent as likely as whites to participate in a mock study to test a pill for heart disease. Results came from a random survey of 717 outpatients at 13 clinics in Maryland, 36 percent of whom were black and the rest white.

Photograph of Participants in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Image courtesy Public Domain Clip Art | The survey is believed to be the first analysis showing that an overestimation of risk of harm explains why blacks’ participation in clinical trials has for decades lagged that of whites. The results come at a time of increased recognition of racial differences in disease rates and treatments. Researchers point out that some kidney diseases, stroke, lung cancer and diabetes all progress more quickly in blacks and kill more blacks than people of other racial backgrounds. |

The infamous Tuskegee study, named after the Alabama town where its participants lived, enrolled several hundred sharecroppers, mostly poor, illiterate blacks, into a study they believed would help treat their syphilis infections. Instead, health care workers denied them available drugs to cure the disease in a secret plan to study the “natural course” of unchecked syphilis. The health care workers were predominantly white.

The government-sponsored experiment ran for 40 years until a leak to the press exposed the deception and the study was shut down in 1972. The resulting public outcry and federal clampdown led to the establishment of federally regulated committees at all American academic centers, so-called institutional review boards, to oversee how clinical studies are designed and to ensure informed consent of all patients.

When the Hopkins researchers probed the perceptions and beliefs behind the decision to participate or stand back among their survey subjects, they found that blacks harbored a strong distrust for physicians when compared to whites:

* 25 percent of blacks thought their physician would be willing to ask them to participate in a study even though the study might harm them, while only 15 percent of whites thought the same;

* 28 percent of blacks, but 22 percent of whites, felt their physician would willingly expose them to unnecessary risk;

* 58 percent of blacks, and 25 percent of whites, thought that physicians use medications to experiment on people without the patient’s consent;

* 8 percent of blacks did not feel comfortable about questioning their physician, while 2 percent of whites were similarly inhibited.

When researchers removed respondents who had feelings of distrust toward physicians from the analysis, the numbers of blacks and whites willing to participate in medical research became the same, at roughly a third of those asked.

“Our results strongly suggest that the problem is the lack of trust and that it may be fixable by communicating better with patients and taking actions that improve mutual respect and understanding,” says Powe, a professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and director of its Welch Center for Prevention, Epidemiology and Clinical Research.

What is not known, says Powe, is how much of the problem is anchored in blacks’ mistrust of society in general and how much of it is influenced by interactions with physicians.

Powe adds that historically low numbers of minority physicians might also play a role in fostering mistrust. Currently, he points out, 12 percent of the U.S. population is black, but only 4 percent of physicians are black. Other studies done by the Hopkins team show that having a physician from the same race fosters patient trust and improves health care satisfaction scores. At Hopkins, the percentage of black medical students since 2000 has ranged between 8 percent and 11 percent.

Joel B. Braunstein, M.D., a research fellow at Hopkins who led the study, says the responsibility for improving the situation rests with physicians and medical schools to reduce the disparity “for the benefit to all of our patients, not just African Americans, but also for medical science in general.”

Braunstein, now a consultant to scientists and investors starting up biomedical companies, recommends, aside from the personal strengthening of relationships between physicians and patients during check-ups, more institutional programs, such as cultural competency programs. He says community projects to promote interaction of academic medical center staff with local neighborhood and business groups might also help.

“The academic medical system exists to help people through discovery and testing of new treatments, and unless people - regardless of race - see research conducted on all types of patients and through their own eyes, they won’t necessarily believe it,” says Powe, whose team plans further research into what types of intervention - physician or patient training, or various community programs - work at improving trust in physicians.

Results from the survey, in which a total of 1,440 people of all races were asked to fill out a questionnaire while they waited for a regularly scheduled check-up, were later broken down so that only the views of blacks and whites could be compared. Every patient was asked by a physician, either white or black, to participate in the mock trial, but only after an in-depth explanation of the risks and benefits involved in joining, including the type of drug under study, possible drug side effects, study length and rules for participants. It was after this vigorous process of simulated informed consent that patients were asked to join up and to explain their rationale for participating or not participating. ###

The study, which took place from April to October 2002, was made possible with funding support provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Other investigators in this research were Noëlle Sherber, M.D.; Steven Schulman, M.D.; and Eric Ding, Sc.D.

For additional information, go to: hopkinsmedicine.org/welchcenter

Contact: David March dmarch1@jhmi.edu 410-955-1534 Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions

Sunday, April 20, 2008

Study: weight-loss tips differ in African-American, mainstream magazines

Malcolm X Boulevard, Lenox Ave. Image courtesy Public Domain Clip Art | Magazines catering to African-Americans may be falling short in their efforts to educate readers about weight loss, a new University of Iowa study suggests. African-American women's magazines are more likely to encourage fad diets and reliance on faith to lose weight, while mainstream women's magazines focus more on evidence-based diet strategies, according to the study by UI researcher Shelly Campo, published in a recent issue of the journal Health Communication. |

Campo and co-author Teresa Mastin, an associate professor in the Department of Advertising, Public Relations, and Retailing at Michigan State University, analyzed 406 fitness and nutrition articles published between 1984 and 2004 in three major African-American women's magazines -- Ebony, Essence and Jet -- and three popular mainstream women's magazines -- Good Housekeeping, Better Homes and Gardens, and Ladies' Home Journal.

The magazines suggested many of the same weight-loss strategies, but mainstream magazines were twice as likely to suggest eating more whole grains and protein, smaller portions, and low-fat foods. Relying on God or faith was suggested by 1 in 10 weight-loss stories in the African-American magazines, but in almost no weight-loss stories in the mainstream magazines.

Fad diets were promoted as legitimate strategies in 15 percent of weight-loss stories in the African-American magazines, compared to only 5 percent in the mainstream magazines. Fad diets, defined as diets that may work in the short term but often do not result in sustained changes, included the Dick Gregory Bahamian Diet, the South Beach Diet, the Hilton Head Diet, and the Atkins Diet.

Mainstream magazines offered more strategies per article than African-American magazines. And, while mainstream magazines increased fitness and nutrition coverage during the second decade as the severity of the obesity epidemic unfolded, African-American magazines did not.

"The study clearly points to a need for public-health advocates and advocates of the African-American community to push their media to increase coverage of overweight and obesity health issues," Campo said.

The research is a companion study to previous work Mastin and Campo published in the Howard Journal of Communications in Oct. 2006. The first study showed that food and nonalcoholic beverage ads outnumbered fitness and nutrition articles 16 to 1 in Ebony, Essence and Jet between 1984 and 2004. The 500 ads were primarily for foods high in calories but low in nutritional value, Campo said.

In the new paper, Campo and Mastin note that both types of magazines tend to place responsibility for weight loss on the individual, rather than examining environmental and economic factors that make weight loss difficult. More than 83 percent of strategies focused on behavior changes, while less than 7 percent focused on environment. For example, magazines recommended eating well and staying active, but rarely addressed issues like availability and cost of healthy food, recreational opportunities in communities, or existence of school- or work-based fitness programs.

"Both genres are highly guilty of over-reliance on individual strategies," Campo said. "We blame individuals too much for circumstances that are not entirely within their control. We know people living in unsafe neighborhoods are much less likely to exercise. And fast food is cheap compared to fresh fruit and vegetables. To tell a poor person that they made a bad choice because they couldn't afford the salad fixings raises some ethical concerns."

African-Americans represent at least 90 percent of the readership of Ebony, Essence and Jet, but 11 percent or less of Better Homes and Gardens, Good Housekeeping and Ladies' Home Journal. The magazines were selected for the study because of their large circulation and longevity over the 20-year period.

STORY SOURCE: University of Iowa News Services, 300 Plaza Centre One, Suite 371, Iowa City, Iowa 52242-2500

Contact: Nicole Riehl nicole-riehl@uiowa.edu 319-384-0070 University of Iowa

Saturday, February 23, 2008

Condoleezza Rice Black History Month VIDEO PODCAST

| Secretary Condoleezza Rice, Dean Acheson Auditorium, Washington, DC. February 22, 2008. FULL STREAMING VIDEO. PODCAST Thank you very much. Thank you. Well, first of all, I’d like to thank Allison for that really kind and wonderful introduction. Allison, thanks also for braving the elements. I’m glad you got here. |

I think none of us can really imagine what it must have been like to be a teenager thrust into history in the way that you were, and of course, you did it with great dignity and with great integrity, and we all have so much that we owe you for having gone through that experience and helping America to come out better on the other side. Thank you for being here. (Applause.) I want to say too that I had a chance to meet your great sister, who is with you. Family is always very important. Thank you for joining us. And I’d like to thank the Office of Civil Rights for the wonderful work in putting all of this together.

Now, I’m going to tell you that perhaps my predecessor many times removed -- I am the 66th Secretary of State of the United States of America -- the first Secretary of State was, of course, Thomas Jefferson. And I think he would have had a hard time imagining this day, let alone Black History Week -- Black History Month, but also that I would be standing here as Secretary of State, a girl from Birmingham, Alabama who grew up in the crucible years of the Civil Rights movement.

Nonetheless, it was Thomas Jefferson, the Secretary of State of many years before, and of course, one of the authors of our great Constitution who, of course, set in place the words and the documents that made it possible for a person like me to one day become the Secretary of State.

But as I think about what this country has gone through, I’m always reminded that what we really represent -- and as I go out and I represent America around the world, what we really represent is evidence that democracy, while hard, and democracy, while always imperfect, is the only system of governance that is worthy of human beings. And it’s worthy because those great principles, those great statements, those great words that were embodied in our Declaration of Independence and our Constitution about the equality of all men and women, were not, of course, fulfilled in the United States for a very long time. Indeed, when the founders said, “We, the people,” they didn’t mean me. On two counts they didn’t mean me.

But of course, we’ve struggled and we’ve come to a second founding with the Civil Rights movement to try to make those words ever more true. And what we really observe in Black History Month is the long trail of dedication and commitment and hard work and, indeed, tears of those who came before us to make it possible for me to stand here as the Secretary of State.

Now I want to tell you a little interesting fact, which is that if I served my full term, it will have been 12 years since the United States of America had a white male Secretary of State, because my predecessors were, of course, Colin Powell, the first African American Secretary – male Secretary of State, and Madeleine Albright, a white woman. And so it shows something that an America whose chief diplomat has been first female, then black, and then black and female has come quite a long way since our friend, Ernest, integrated Little Rock High. (Applause.)

Now we are, of course, in foreign policy, building on the shoulders of greats: Carl Rowan and Ralph Bunche and Terence Todman and Patricia Roberts Harris, Colin Powell himself and of course, people who continue that tradition like our great ambassador, Ruth Davis, who we all keep in our prayers and wish well and of course, Harry Thomas, who is a trailblazer in his own right. They’re all testament to the doors that have been opened along our nation’s path to a more perfect union.

Now I’m very proud that the State Department has been a part of that tradition since our diplomatic corps was diversified in 1949 when Edward Dudley went to serve in Liberia as the first African American Ambassador. And the Department of State is, of course, the first Cabinet agency to establish the position of Chief Diversity Officer, very important because we have been trying very hard to double the number of people at the Department through the Rangel Fellows program here at the Department. We’ve doubled that fellowship program. We’ve had great success with Congressman Rangel in trying to target students at schools with large minority populations. We’ve got diplomats posted at places like Howard and Florida A&M and Morehouse and Spelman College so that senior Foreign Service Officers can talk about what it means to be a member of this Foreign Service.

Now I want to tell you why we do that. We do that because our country has come to recognize the value of diversity. There is no doubt about that. We also do it because there is a moral obligation to make certain that our ranks are open to America’s finest no matter race, color, creed, nationality and that’s why we do these things. But we also do it for a very important reason. It is essential to who we are as the Department of State, the representatives of American foreign policy.

When I go out around the world and I go to places – I was just in Africa yesterday and I’ll be in Asia tomorrow – and when I go around and I look at places trying to make that journey from conflict perhaps, from, in some cases, civil war, in other cases, just repression and tyranny, I recognize that one of the hardest things to get right is the relationship between people who are different. We all share a common humanity. We all share a universal desire that we will be treated with dignity, that we will be able to educate our children, boys and girls, that we will be able to speak our conscience and our mind, that we will be able to worship freely, that we will be able to select those who are going to govern us. Those are all things that we share in our common humanity.

But for some reason, we look different on the outside despite the fact that that core is very much the same. And one of the hardest things that human beings have had to come to terms with is that that inner core is what counts, not what is on the outside. And so as I go around the world and I watch countries trying to come to terms with difference and when I sometimes go to places where difference has, in fact, been a license to kill, I’m reminded that there is no more important lesson than the journey of America, a great multiethnic democracy that started out with the birth defect of slavery and that, today, has come as far as it has come, but recognizes that even our journey is not complete.

And so when I go into these rooms, I want our diplomatic corps to look like America. I want our diplomatic corps to show all of the faces of America, to speak with the voice of American, but to look like the world because that’s who we are as a country. And it just doesn’t work to go into a room and see very few people who look like me in our diplomatic corps.

And so I’m going to close with an appeal maybe to some of the young folks in our choir, maybe to some of the young folks who are interns here or are sitting here and listening: Come and join America’s Foreign Service. Become a part of the diplomatic corps that represents America and its ideals, because we can talk about equality evolved, we can talk about diversity as a strength, we can talk about the fact that difference should not be a reason to separate, but a reason to unite. But unless we look like we mean it, we’re never going to be fully believed. And so I’ll admit it’s a commercial. (Laughter.) When you talk to young people, when you mentor young people, tell them what a great career you can have in representing this great country. Because there is one thing that we know: It is a country that rewards now merit; it is a country in which you can achieve; it is still a country that is trying to get right its very, very special principles of equality for all, of justice for all, and for inclusion of all.

And so if I have one thing that I hope I can continue to work for long after I’ve left this post, it is that when America greets the world, she will greet the world with her full glory of diversity and difference, but her common humanity and belief in the great values that have made this country possible and which so many others still seek.

Thank you very much. (Applause.)

2008/133, Released on February 22, 2008

Tags: Secretary Condoleezza Rice and Black History Month

Wednesday, February 13, 2008

Anthony Burns the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

| Digital ID: cph 3b37099 Source: b&w film copy neg. Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-90750 (b&w film copy neg.) Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieve uncompressed archival TIFF version (1,688 kilobytes) TITLE: Anthony Burns / John Andrews, sc. CALL NUMBER: PGA - Andrews--Anthony Burns (B size) [P&P] REPRODUCTION NUMBER: LC-USZ62-90750 (b&w film copy neg.) |

SUMMARY: A portrait of the fugitive slave Anthony Burns, whose arrest and trial under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 touched off riots and protests by abolitionists and citizens of Boston in the spring of 1854. A bust portrait of the twenty-four-year-old Burns, "Drawn by Barry from a daguereotype [sic] by Whipple and Black," is surrounded by scenes from his life. These include (clockwise from lower left): the sale of the youthful Burns at auction, a whipping post with bales of cotton, his arrest in Boston on May 24, 1854, his escape from Richmond on shipboard, his departure from Boston escorted by federal marshals and troops, Burns's "address" (to the court?), and finally Burns in prison. Copyrighting works such as prints and pamphlets under the name of the subject (here Anthony Burns) was a common abolitionist practice. This was no doubt the case in this instance, since by 1855 Burns had in fact been returned to his owner in Virginia.

MEDIUM: 1 print on wove paper: wood engraving with letterpress ; sheet 42.8 x 33.2 cm. CREATED, PUBLISHED: [Boston] : R.M. Edwards, printer, 129 Congress Street, Boston, c1855.

CREATOR: Andrews, John, engraver. NOTES: Title from item. "Entered ... 1855, by Anthony Burns ... Massachusetts." The Library's impression was deposited for copyright on January 25, 1855. DLC

Published in: American political prints, 1766-1876 / Bernard F. Reilly. Boston : G.K. Hall, 1991, entry 1855-3. REPOSITORY: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

DIGITAL ID: (b&w film copy neg.) cph 3b37099 http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3b37099 CONTROL #: 2003689280

Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Fugitive Slave Law or Fugitive Slave Act was passed by the United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern slaveholding interests and Northern Free-Soilers. This was one of the most controversial acts of the 1850 compromise and heightened Northern fears of a 'slave power conspiracy'.

This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia article, Fugitive Slave Law of 1850

Monday, February 4, 2008

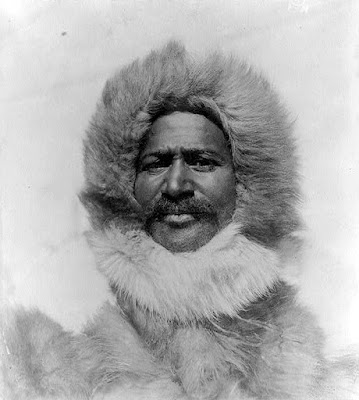

Matthew Alexander Henson

TITLE: [Matthew Alexander Henson, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing front, wearing fur hat and fur coat] CALL NUMBER: BIOG FILE - Henson, Matthew Alexander, 1866-1955 [item] [P&P] REPRODUCTION NUMBER: LC-USZC4-7503 (color film copy transparency) LC-USZ62-42993 (b&w film copy neg.)

RIGHTS INFORMATION: No known restrictions on publication.

MEDIUM: 1 photographic print. CREATED, PUBLISHED: c1910. NOTES: J137917 U.S. Copyright Office.

REPOSITORY: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, DIGITAL ID: (color film copy transparency) cph 3g07503 hdl.loc.gov/cph.3g07503 (b&w film copy neg.) cph 3a43309 hdl.loc.gov/cph.3a43309, CONTROL #: 00650163

Credit Line: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, [reproduction number, LC-USZC4-7503]

| MARC Record Line 540 - No known restrictions on publication. Works published prior to 1978 were copyright protected for a maximum of 75 years. See Circular 1 "COPYRIGHT BASICS" from the U.S. Copyright Office. Works published works before 1923 are now in the public domain. Matthew Henson From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Matthew Alexander Henson (August 8, 1866 – March 9, 1955) was an American explorer and long-time companion to Robert Peary; amongst various expeditions, their most famous was a 1909 expedition which claimed to be the first to reach the Geographic North Pole. |

Matthew Henson was born on a farm in a rural Maryland county in 1866. He was still a child when his parents Lemuel and Caroline died, and at the age of twelve he went to sea as a cabin boy on a merchant ship. He sailed around the world for the next several years, educating himself and becoming a skilled navigator. Henson met Commander Robert R. Peary in 1888 and joined him on an expedition to Nicaragua. Impressed with Henson’s seamanship, Peary recruited him as a colleague.

For years they made many trips together, including Arctic voyages in which Henson traded with the Eskimos and mastered their language, built sleds, and trained dog teams. In 1909, Peary mounted his eighth attempt to reach the North Pole, selecting Henson to be one of the team of six who would make the final run to the Pole. Before the goal was reached, Peary could no longer continue on foot and rode in a dog sled.

Various accounts say he was ill, exhausted, or had frozen toes. In any case, he sent Henson on ahead as a scout. In a newspaper interview Henson said: “I was in the lead that had overshot the mark a couple of miles. We went back then and I could see that my footprints were the first at the spot.” Henson then proceeded to plant the American flag.

Although Admiral Peary received many honors, Henson was largely ignored and spent most of the next thirty years working as a clerk in a federal customs house in New York. But in 1944 Congress awarded him a duplicate of the silver medal given to Peary. Presidents Truman and Eisenhower both honored him before he died in 1955.

In 1912 Henson wrote the book A Negro Explorer at the North Pole about his arctic exploration. Later, in 1947 he collaborated with Bradley Robinson on his biography Dark Companion. The 1912 book, along with an abortive lecture tour, enraged Peary who had always considered Henson no more than a servant and saw the attempts at publicity as a breach of faith.

This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia article, Matthew Henson

Technorati tags: Why the web tells us what we already know and Chinese New Year of the Rat, Wu Zi, 4705 and Nanowires hold promise for more affordable solar cells or Harriet Tubman

Friday, January 25, 2008

Harriet Tubman

TITLE: [Harriet Tubman, full-length portrait, seated in chair, facing front, probably at her home in Auburn, New York], CALL NUMBER: Illus. in JK1881 .N357 sec. 16, No. 9 NAWSA Coll [Rare Book RR], REPRODUCTION NUMBER: LC-DIG-ppmsca-02909 (scan from color copy photo in Publishing Office), No known restrictions on publication. MEDIUM: 1 photographic print. CREATED, PUBLISHED: [1911]

Digital ID: ppmsca 02909 Source: scan from color copy photo in Publishing Office Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-ppmsca-02909 (scan from color copy photo in Publishing Office) Repository: Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

NOTES: Illus. in: Scrapbooks of Elizabeth Smith Miller and Anne Fitzhugh Miller / Elizabeth Smith Miller. New York : Geneva, 1897-1911, section 16, no. 9, p. 47. National American Woman Suffrage Association Collection (Library of Congress).

Published in: American women : a Library of Congress guide for the study of women's history and culture in the United States / edited by Sheridan Harvey ... [et al.]. Washington : Library of Congress, 2001, p. 417.

| Retrieve higher resolution JPEG version (166 kilobytes) MARC Record Line 540 - No known restrictions on publication. REPOSITORY: Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA , DIGITAL ID: (scan from color copy photo in Publishing Office) ppmsca 02909 hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/, CARD #: 2002716779 Works published prior to 1978 were copyright protected for a maximum of 75 years. See Circular 1 "COPYRIGHT BASICS" from the U.S. Copyright Office. Works published works before 1923 are now in the public domain. Credit Line: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, [reproduction number, LC-DIG-ppmsca-02909] |

Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman (born Araminta Ross, c. 1820 – 10 March 1913) was an African-American abolitionist, humanitarian, and Union spy during the U.S. Civil War. After escaping from captivity, she made thirteen missions to rescue over three hundred slaves using the network of antislavery activists and safe houses known as the Underground Railroad. She later helped John Brown recruit men for his raid on Harpers Ferry, and in the post-war era struggled for women's suffrage.

Born into slavery in Dorchester County, Maryland, Tubman was beaten and whipped by her various owners as a child. Early in her life, she suffered a traumatic head wound when an irate slave owner threw a heavy metal weight at her, intending to hit another slave. The injury caused disabling seizures, headaches, and powerful visionary and dream activity, and spells of hypersomnia which occurred throughout her entire life. A devout Christian, she ascribed her visions and vivid dreams to premonitions from God.

In 1849, Tubman escaped to Philadelphia, then immediately returned to Maryland to rescue her family. Slowly, one group at a time, she brought relatives with her out of the state, and eventually guided dozens of other slaves to freedom. Traveling by night and in extreme secrecy, Tubman (or "Moses", as she was called) "never lost a passenger". Heavy rewards were offered for many of the people she helped bring away, but no one ever knew it was Harriet Tubman who was helping them. When a far-reaching United States Fugitive Slave Law was passed in 1850, she helped guide fugitives further north into Canada, and helped newly-freed slaves find work.

When the U.S. Revolutionary War began, Tubman worked for the Union Army, first as a cook and nurse, and then as an armed scout and spy. The first woman to lead an armed expedition in the war, she guided the raid on the Combahee River, which liberated more than seven hundred slaves. After the war, she retired to the family home in Auburn, New York, where she cared for her aging parents. She was active in the women's suffrage movement until illness overtook her and she had to be admitted to a home for elderly African-Americans she had helped open years earlier. After she died in 1913, she became an icon of American courage and freedom.

Harriet Tubman was born Araminta "Minty" Ross to slave parents, Harriet ("Rit") Green and Ben Ross. Rit was owned by Mary Pattison Brodess (and later her son Edward), while Ben was legally owned by Mary's second husband, Anthony Thompson, who ran a large plantation near the Blackwater River in Dorchester County, Maryland. As with many slaves in the United States, neither the exact year nor place of her birth was recorded, and historians differ as to the best estimate. Kate Larson records the year 1822, based on a midwife payment and several other historical documents while Jean Humez says "the best current evidence suggests that Tubman was born in 1820, but it might have been a year or two later." Catherine Clinton notes that Tubman herself reported the year of her birth as 1825, while her death certificate lists 1815 and her gravestone lists 1820. In her Civil War widow's pension record, Tubman claimed she was born in 1820, 1822, and 1825, an indication, perhaps, that she had no idea when she was born.

Modesty, Tubman's maternal grandmother, arrived in the US on a slave ship from Africa; no information is available about her other ancestors. As a child, Tubman was told that she was of Ashanti lineage (from what is now Ghana), though no evidence exists to confirm or deny this assertion. Her mother Rit (who may have been the child of a white man) was a cook for the Brodess family. Her father Ben was a skilled woodsman who managed the timber work on the plantation. They married around 1808, and according to court records, they had nine children together: Linah, born in 1808, Mariah Ritty in 1811, Soph in 1813, Robert in 1816, Minty (Harriet) in 1822, Ben in 1823, Rachel in 1825, Henry in 1830, and Moses in 1832.

Rit struggled to keep their family together as slavery tried to tear it apart. Edward Brodess sold three of her daughters (Linah, Mariah Ritty, and Soph), separating them from the family forever. When a trader from Georgia approached Brodess about buying Rit's youngest son Moses, she hid him for a month, aided by other slaves and free blacks in the community. At one point she even confronted her owner about the sale. Finally, Brodess and "the Georgia man" came toward the slave quarters to seize the child, where Rit told them: "You are after my son; but the first man that comes into my house, I will split his head open." Brodess backed away and abandoned the sale. Tubman's biographers agree that tales of this event in the family's history influenced her belief in the possibilities of resistance.

This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia article, Harriet Tubman

Republican debate Boca Raton, Florida 01/24/08 VIDEO and MINI (BMW) parallel Mini Coopers and Washington University, 2 industries, team to clean up mercury emissions or Booker T. Washington

Thursday, January 24, 2008

Booker T. Washington

TITLE: [Booker T. Washington, half-length portrait, seated at desk, facing right], CALL NUMBER: LOT 13164-A, no. 10 [P and P], REPRODUCTION NUMBER: LC-USZ62-119898 (b and w film copy neg.)LC-USZ62-36291 (b and w film copy neg.)

Digital ID: cph 3c19898 Source: b and w film copy neg. Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-119898 (b&w film copy neg.) , LC-USZ62-36291 (b and w film copy neg.) Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA Retrieve higher resolution JPEG version (86 kilobytes)

January 15, 1901, Republican Booker T. Washington protests Alabama Democratic Party’s refusal to permit voting by African-Americans. Freedom Calendar 01/14/06 - 01/21/06

MEDIUM: 1 photographic print. CREATED/PUBLISHED: [between 1890 and 1910], NOTES: Booker T. Washington Collection (Library of Congress).

REPOSITORY: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA.

Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856 – November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author and leader of the African American community. He was freed from slavery as a child, gained an education, and as a young man was appointed to lead a teachers' college for blacks. From this position of leadership he rose into a nationally prominent role as spokesman for African Americans.

Washington was born into slavery to a white father, about whom he knew little, and a black slave mother on a rural farm in southwest Virginia. This made him mixed race as are, to one degree or another (as a result of the chattel legacy), many African Americans; yet the so-called "one drop rule" ensured that he grew up in the social category of Negro. He was freed in 1865 at the end of the Civil War by the Thirteenth Amendment. After working in saltfurnaces and coalmines in West Virginia for several years, he made his way east to a school which became Hampton University. There, he worked his way through, later attending Wayland Seminary to return as an instructor. In 1881, he was recommended by Hampton president Samuel C. Armstrong to become the first leader of the new normal school (teachers' college) which became Tuskegee University in Alabama, where he served the rest of his life.

Washington was the dominant figure in the African American community in the United States from 1890 to 1915, especially after he achieved prominence for his Atlanta Address of 1895. To many politicians and the public in general, he was seen as a popular spokesperson for African American citizens. Representing the last generation of black leaders born into slavery, he was generally perceived as a credible proponent of educational improvements for those freedmen who had remained in the post-Reconstruction, Jim Crow South. Throughout the final 20 years of his life, he maintained this standing through a nationwide network of core supporters in many communities, including black educators, ministers, editors and businessmen, especially those who were liberal-thinking on social and educational issues. He gained access to top national leaders in politics, philanthropy and education, and was awarded honorary degrees. Critics called his network of supporters the "Tuskegee Machine."

Late in his career, Washington was criticized by the leaders of the NAACP, which was formed in 1909, especially W.E.B. Du Bois, who demanded a harder line on civil rights protests. After being labeled "The Great Accommodator" by Du Bois, Washington replied that confrontation would lead to disaster for the outnumbered blacks, and that cooperation with supportive whites was the only way to overcome pervasive racism in the long run. Although he did some aggressive civil rights work secretively, such as funding court cases, he seemed to truly believe in skillful accommodation to many of the social realities of the age of segregation. While apparently resigned to many undesirable social conditions in the short term, he also clearly had his eyes on a better future for blacks. Through his own personal experience, Washington knew that good education was a major and powerful tool for individuals to collectively accomplish that better future.

Washington's philosophy and tireless work on education issues helped him enlist both the moral and substantial financial support of many philanthropists. He became friends with such self-made men from modest beginnings as Standard Oil magnate Henry Huttleston Rogers and Sears, Roebuck and Company President Julius Rosenwald. These individuals and many other wealthy men and women funded his causes, such as supporting the institutions of higher education at Hampton and Tuskegee. Each school was originally founded to produce teachers. However, graduates had often gone back to their local communities only to find precious few schools and educational resources to work with in the largely impoverished South. To address those needs, through provision of millions of dollars and innovative matching funds programs, Washington and his philanthropic network stimulated local community contributions to build small community schools. Together, these efforts eventually established and operated over 5,000 schools and supporting resources for the betterment of blacks throughout the South in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The local schools were a source of much community pride and were of priceless value to African-American families during those troubled times in public education. This work was a major part of his legacy and was continued (and expanded through the Rosenwald Fund and others) for many years after Washington's death in 1915.

Washington did much to improve the overall friendship and working relationship between the races in the United States. His autobiography, Up From Slavery, first published in 1901, is still widely read today.

This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia article, Booker T. Washington

Wednesday, January 23, 2008

George Washington Carver

"George Washington Carver was born about sixty years ago of slave parents on the Missouri farm of Moses Carver (whose name, after the fashion of slaves, the mother of the son bore). Carver's earliest recollections were the death of his father and the stealing of himself and his mother by a band of raiders in the last year of the Civil War. Moses Carver, whom George W. Carver remembers as his kindly master, sent a rescuing party on horseback liberally provided with funds to buy their release, but when the searchers overtook the marauders in Arkansas, Mary Carver, the mother, had disappeared and was never again heard from. Little George was found grievously ill with whooping cough. A race horse valued at $300 was given in exchange for him and he was returned to the Missouri farm where he was reared by his master.

Like Booker T. Washington, Carver became the rich possessor of one book, an old blue-backed speller. This he soon learned by heart, as he mastered his letters; but opportunity did not seek him out. He was forced to accept the limitations of the spelling book until he was ten years old, at which time he found his way to a Negro school eight miles away. Lodging in the cabins of friendly Negroes, sleeping in open fields or in a hospitable stable, he continued his studies for a year, keeping ever close to the soil. After graduating from this school, he set out toward Kansas, "the home of the free." A mule team overtook him a day's journey out and took him into Fort Scott where his definite schooling was begun. For nine years he worked as a domestic servant, studying day and night as his employment permitted. He specialized in laundry work and when he next moved forward he was able by the careful management and utmost frugality to complete a high-school course at Minneapolis, Kan.

After graduating from high school, Carver entered Iowa State College. Along with his studies here much of his time was given over to the management of a laundry out of which he earned enough money to meet his school expenses. Completing the work for his Bachelor's and Master's degrees, he was graduated and made a member of the faculty in charge of the greenhouse, the bacteriological laboratory, and the department of systematic botany."

TITLE: [George Washington Carver, full-length portrait, seated on steps (bottom center), facing front, with staff], CALL NUMBER: LOT 13164-C, no. 103 [P&P]

REPRODUCTION NUMBER: LC-DIG-ppmsca-05633 (digital file from modern print), No known restrictions on publication.

Digital ID: ppmsca 05633 Source: digital file from modern b&w print Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-ppmsca-05633 (digital file from modern print) Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA Retrieve higher resolution JPEG version (147 kilobytes)

MEDIUM: 1 photographic print. CREATED, PUBLISHED: [ca. 1902], CREATOR: Johnston, Frances Benjamin, 1864-1952, photographer.

NOTES: Title devised by Library staff. Reference copy (modern print) in BIOG FILE - Carver, George Washington. Forms part of: Booker T. Washington Collection (Library of Congress). Original negative may be available: LC-J694-159.

| Works published prior to 1978 were copyright protected for a maximum of 75 years. See Circular 1 "COPYRIGHT BASICS" PDF from the U.S. Copyright Office. Works published works before 1923 (THIS IMAGE) are now in the public domain. |

MARC Record Line 540 - No known restrictions on publication.

Credit Line: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, [reproduction number, LC-DIG-ppmsca-05633]

George Washington Carver

George Washington Carver (July 12, 1864 – January 5, 1943) was an American botanical researcher and agronomy educator who worked in agricultural extension at the Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama, teaching former slaves farming techniques for self-sufficiency.

To bring education to farmers, Carver designed a mobile school. It was called a Jesup Wagon after the New York financier, Morris Ketchum Jesup, who provided funding. In 1921, Carver spoke in favor of a peanut tariff before the House Ways and Means Committee. Given racial discrimination of the time, it was unusual for an African-American to be called as an expert. Carver's well-received testimony earned him national attention, and he became an unofficial spokesman for the peanut industry. Carver wrote 44 practical agricultural bulletins for farmers.

In the post-Civil-War South, an agricultural monoculture of cotton had depleted the soil, and in the early 1900s, the boll weevil destroyed much of the cotton crop. Much of Carver's fame was based on his research and promotion of alternative crops to cotton, such as peanuts and sweet potatoes. He wanted poor farmers to grow alternative crops as both a source of their own food and a cash crop. His most popular bulletin contained 105 existing food recipes that used peanuts. His most famous method of promoting the peanut involved his creation of about 100 existing industrial products from peanuts, including cosmetics, dyes, paints, plastics, gasoline and nitroglycerin. His industrial products from peanuts excited the public imagination but none was a successful commercial product. There are many myths about Carver, especially the myth that his industrial products from peanuts played a major role in revolutionizing Southern agriculture.

Carver's most important accomplishments were in areas other than industrial products from peanuts, including agricultural extension education, improvement of racial relations, mentoring children, poetry, painting, religion, advocacy of sustainable agriculture and appreciation of plants and nature. He served as a valuable role model for African-Americans and an example of the importance of hard work, a positive attitude and a good education. His humility, humanitarianism, good nature, frugality and lack of economic materialism have also been widely admired.

One of his most important roles was that the fame of his achievements and many talents undermined the widespread stereotype of the time that the black race was intellectually inferior to the white race. In 1941, "Time" magazine dubbed him a "Black Leonardo," a reference to the white polymath Leonardo da Vinci.

This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia article, George Washington Carver

The Federal Open Market Committee lowers funds rate 75 basis points and 125th St. Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and Feeling the Heat: Berkeley Researchers Make Thermoelectric Breakthrough in Silicon Nanowires or Jack Johnson Heavyweight Champion of the World

Tuesday, January 22, 2008

Jack Johnson Heavyweight Champion of the World

| TITLE: Jack Johnson / D.W.A. photo. CALL NUMBER: LOT 10816 SUMMARY: Jack Johnson, boxer, full-length portrait, standing in ring, facing slightly right., MEDIUM: 1 photographic print., CREATED/PUBLISHED: [between 1910 and 1915] SUBJECTS: Johnson, Jack, 1878-1946. and Boxers (Sports)--1910-1920., DIGITAL ID: (b&w film copy neg.) cph 3d01823 hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ CARD #: 93501352 |

Credit Line: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number, LC-USZ6-1823]

MARC Record Line 540 - No known restrictions on publication.

Works published prior to 1978 were copyright protected for a maximum of 75 years. See Circular 1 "COPYRIGHT BASICS" from the U.S. Copyright Office. Works published works before 1923 are now in the public domain.

Jack Johnson (boxer) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

John Arthur Johnson (March 31, 1878 – June 10, 1946), better known as Jack Johnson and nicknamed the “Galveston Giant”, was an American boxer and arguably the best heavyweight of his generation. He was the first black Heavyweight Champion of the World (1908-1915), a feat which, for its time, was tremendously controversial. In a documentary about his life, Ken Burns said: “For more than thirteen years, Jack Johnson was the most famous, and the most notorious African-American on Earth

Jack Johnson was born in Galveston, Texas as the second child and first son of Henry and Tina “Tiny” Johnson, former slaves and faithful Methodists, who both worked blue-collar jobs to earn enough to raise six children (the Johnsons had nine children, five of whom lived to adulthood, and an adopted son) and taught them how to read and write. Jack Johnson had five years of formal education. He was later kicked out of church when he stated that God did not exist and that the church was a domination over people's lives.[citation needed]

Johnson fought his first bout, a 16-round victory, at age 15. He turned professional around 1897, fighting in private clubs and making more money than he had ever seen. In 1901, Joe Choynski, the small Jewish heavyweight, came to Galveston to train Jack Johnson. Choynski, an experienced boxer, knocked Johnson out in round three, and the two were arrested for "engaging in an illegal contest" and put in jail for 23 days. (Although boxing was one of the three most popular sports in America at the time, along with baseball and horse-racing, the practice was officially illegal in most states, including Texas.) Choynski began training Johnson in jail but did not get arrested.

Johnson's fighting style was very distinctive. He developed a more patient approach than was customary in that day: playing defensively, waiting for a mistake, and then capitalizing on it. Johnson always began a bout cautiously, slowly building up over the rounds into a more aggressive fighter. He often fought to punish his opponents rather than knock them out, endlessly avoiding their blows and striking with swift counters. He always gave the impression of having much more to offer and, if pushed, he could punch quite powerfully. Johnson's style was very effective, but it was criticized in the white press as being cowardly and devious. In contrast, World Heavyweight Champion "Gentleman" Jim Corbett, who was white, had used many of the same techniques a decade earlier, and was praised by the white press as "the cleverest man in boxing."

By 1902, Johnson had won at least 50 fights against both white and black opponents. Johnson won his first title on February 3, 1903, beating "Denver" Ed Martin over 20 rounds for the World Colored Heavyweight Championship. His efforts to win the full title were thwarted as World Heavyweight Champion James J. Jeffries refused to face him. Blacks could box whites in other arenas, but the heavyweight championship was such a respected and coveted position in America that blacks were not deemed worthy to compete for it. Johnson was, however, able to fight former champion Bob Fitzsimmons in July 1907, and knocked him out in two rounds.

He eventually won the World Heavyweight Title on December 26, 1908, when he fought the Canadian world champion Tommy Burns in Sydney, Australia, after following him all over the world, taunting him in the press for a match. The fight lasted fourteen rounds before being stopped by the police in front of over 20,000 spectators. The title was awarded to Johnson on a referee's decision as a T.K.O, but he had severely beaten the champion. During the fight, Johnson had mocked both Burns and his ringside crew. Every time Burns was about to go down, Johnson would hold him up again, punishing him more. The camera was stopped just as Johnson was finishing off Burns, so as not to show Burns' defeat.

This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia article, Jack Johnson (boxer)

Technorati tags: Jack Johnson Heavyweight Champion and President Visits Martin Luther King, Jr., Memorial Library VIDEO PODCAST and Ebenezer Baptist Church and Nanotechnology innovation may revolutionize gene detection in a single cell

Monday, January 21, 2008

Ebenezer Baptist Church

Ownership: Information presented on this website, (THIS IMAGE) unless otherwise indicated , is considered in the public domain. It may may be distributed or copied as is permitted by the law. Martin Luther King Jr National Historic Site>

Throughout its long history, Ebenezer Baptist Church has been a spiritual home to many citizens of the "Sweet Auburn" community.

Its most famous member, Martin Luther King, Jr., was baptized as a child in the church. After giving a trial sermon to the congregation at Ebenezer at the age of 19 Martin was ordained as a minister. In 1960 Dr. King, Jr. became a co-pastor of Ebenezer with his father, "Daddy" King. He remained in that position until his death in 1968. As a final farewell to his spiritual home Dr. King, Jr.'s funeral was held in the church.

Phase II of the project will restore the appearance of the sanctuary and fellowship hall to the 1960-68 period when Dr. King served as co-pastor with his father.

Special work items include preservation of stain glass windows; restoration/replication of furnishings; repair of balcony structural system; rehabilitation of restrooms; abatement of asbestos-containing flooring; treatment of termite infestation/damage; installation of a lightning protection system; improvement of site drainage; and restoration of a sidewalk, baptistery, and pipe organ and its antiphonal.

A scheduled date for Phase II has yet to be determined. Historic Ebenezer Baptist Church to Close for Repairs

RELATED:

Saturday, January 19, 2008

Martin Luther King jr.

SUBJECTS: King, Martin Luther, Jr., 1929-1968. FORMAT: Portrait photographs 1960-1970. Photographic prints 1960-1970. PART OF: New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

REPOSITORY: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. DIGITAL ID: (b&w film copy neg.) cph 3c26559.hdl.loc.gov/cph.3c26559. CONTROL #: 00651714

Martin Luther King, Jr. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Martin Luther King, Jr. (January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968), was one of the main leaders of the American civil rights movement. King was a Baptist minister, one of the few leadership roles available to black men at the time. He became a civil rights activist early in his career. He led the Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955 - 1956) and helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (1957), serving as its first president. His efforts led to the 1963 March on Washington, where King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech. Here he raised public consciousness of the civil rights movement and established himself as one of the greatest orators in U.S. history. In 1964, King became the youngest person to receive the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to end segregation and racial discrimination through civil disobedience and other non-violent means.

King's nonviolent philosophy contrasted with that of Malcolm X and other black activists who embraced violent resistance. He faced criticism not only from white racists but from violent black activists.

King was assassinated on April 4, 1968, in Memphis, Tennessee. He was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Jimmy Carter in 1977. Martin Luther King Day was established as a national holiday in the United States in 1986. In 2004, King was posthumously awarded a Congressional Gold Medal.[

Martin Luther King, Jr., was born on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia. He was the son of Reverend Martin Luther King, Sr. and Alberta Williams King. Although Dr. King's name was mistakenly recorded as "Michael King" on his birth certificate, this was not discovered until 1934, when his father applied for a passport. He had an older sister, Willie Christine (September 11, 1927) and a younger brother, Alfred Daniel (July 30, 1930 – July 1, 1969).

King sang with his church choir at the 1939 Atlanta premiere of the movie Gone with the Wind. He entered Morehouse College at age fifteen, skipping his ninth and twelfth high school grades without formally graduating.

In 1948, he graduated from Morehouse with a Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) degree in sociology, and enrolled in Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, and graduated with a Bachelor of Divinity (B.D.) degree in 1951. In September 1951, King began doctoral studies in systematic theology at Boston University and received his Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) on June 5, 1955.

This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia article, Martin Luther King, Jr.

Friday, January 18, 2008

Frederick Douglass

ARC Identifier: 558770. Local Identifier: FL-FL-22. Title: Frederick Douglass, ca. 1879. Creator: Legg, Frank W. ( Most Recent) Type of Archival Materials: Photographs and other Graphic Materials.

Level of Description: Item from Collection FL: FRANK W. LEGG PHOTOGRAPHIC COLLECTION OF PORTRAITS OF NINETEENTH-CENTURY NOTABLES, 1862 - 1884

Location: Still Picture Records LICON, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S), National Archives at College Park, 8601 Adelphi Road, College Park, MD 20740-6001

PHONE: 301-837-3530, FAX: 301-837-3621, EMAIL: stillpix@nara.gov. Production Date: ca. 1879. Part of: Series: Portraits, 1862 - 1884. High Resolution Image (2,089 × 3,000 pixels, file size: 1.11 MB, MIME type: image/jpeg)

Access Restrictions: Unrestricted. Use Restrictions: Unrestricted.

General Note: Use War and Conflict Number 113 when ordering a reproduction or requesting information about this image. Variant Control Number(s): NAIL Control Number: NWDNS-200-FL-22. NAIL Control Number: NWDNS-FL-FL-22.

Renowned for his eloquence, he lectured throughout the US and England on the brutality and immorality of slavery. As a publisher his North Star and Frederick Douglass' Paper brought news of the anti-slavery movement to thousands. Forced to leave the country to avoid arrest after John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, he returned to become a staunch advocate of the Union cause. He helped recruit African American troops for the Union Army, and his personal relationship with Lincoln helped persuade the President to make emancipation a cause of the Civil War. Two of Douglass' sons served in the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, which was made up entirely of African American volunteers. The storming of Fort Wagner by this regiment was dramatically portrayed in the film Glory! A painting of this event hangs in the front hall at Cedar Hill.

All of Douglass' children were born of his marriage to Anna Murray. He met Murray, a free African American, in Baltimore while he was still held in slavery. They were married soon after his escape to freedom. After the death of his first wife, Douglass married his former secretary, Helen Pitts, of Rochester, NY. Douglass dismissed the controversy over his marriage to a white woman, saying that in his first marriage he had honored his mother's race, and in his second marriage, his father's.

In 1872, Douglass moved to Washington, DC where he initially served as publisher of the New National Era, which was intended to carry forward the work of elevating the position of African Americans in the post-Emancipation period. This enterprise was discontinued when the promised financial backing failed to materialize. In this period Douglass also served briefly as President of the Freedmen's National Bank, and subsequently in various national service positions, including US Marshal for the District of Columbia, and diplomatic positions in Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Frederick Douglass National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service)

TEXT CREDIT: Ownership Information presented on this website, unless otherwise indicated , is considered in the public domain. It may may be distributed or copied as is permitted by the law. U.S. National Park Service Disclaimer